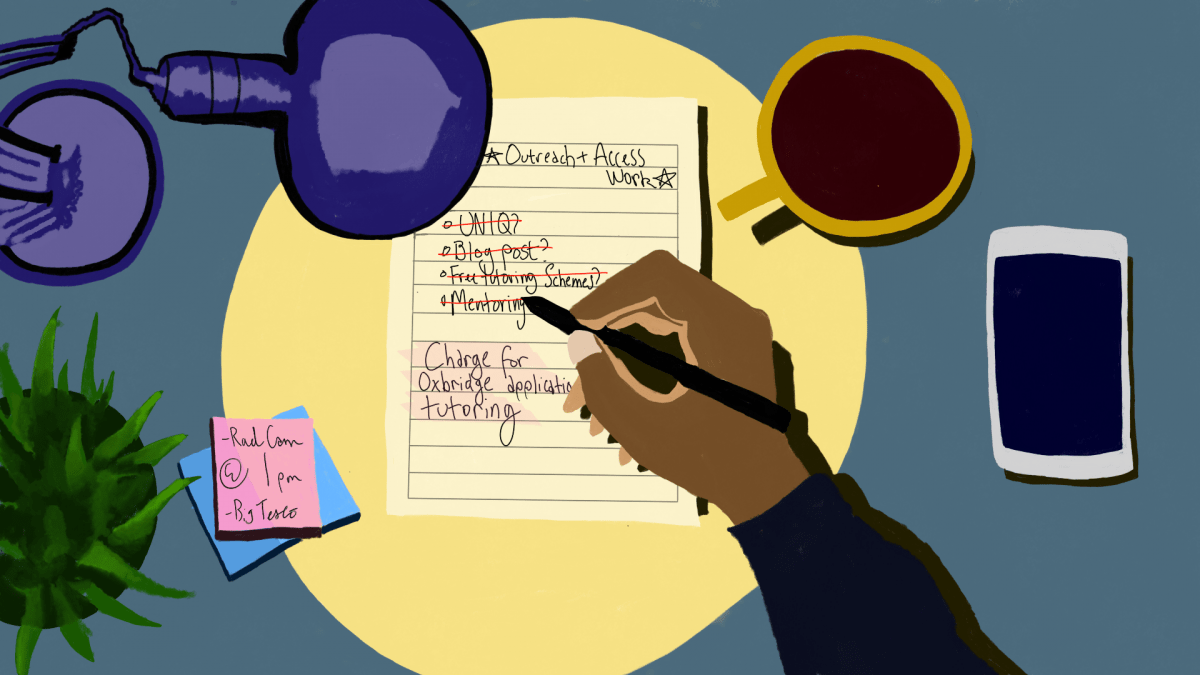

Illustration by Eliott Rose

As another cohort of freshers get ready to move to Oxford, us returning students can reminisce about how we felt when we were in their shoes. Personally, I was filled with dread over moving down South and engaging with people who can’t locate Manchester on a map, but for most normal people I imagine it was a sense of excitement and trepidation about embarking on this new chapter of life.

Many – I would even venture to say most – of us will have worked our little cotton (I’m sure some prefer cashmere) socks off in order to secure a place here, but naturally some people would have had more help and guidance than others. Of course, top private school education is often considered to be the main source of advantage in this area of Oxbridge / university guidance, but there is another way privileged students try to beat the system: private tutoring.

You may remember the stalls and reps from university open days where Oxbridge mentoring and summer schools are pushed to prospective students. Seeing such services so heavily promoted whilst knowing that I would be unable to afford to use them did contribute a little to the imposter syndrome I had before I had even applied. Oxford and Cambridge may not officially endorse these businesses, but seeing them plastered about everywhere really does give the impression that admission to Oxbridge is a possibility if you can afford it.

I can’t help but feel rather sceptical when I see other students decide to work for these private summer schools, fee-charging Oxbridge mentoring organisations and even deciding to offer application guidance as a sort of freelance tutor. Doing access work which charges a fee is not access. It is gatekeeping information about the world of academia to those who can afford it, and no doubt many of those who can afford it are those whose parents send them to top private schools or selective grammars in pricey catchment areas. By choosing to support a student who can afford it, you have prioritised giving them advantages over a student who can’t.

Indeed, the normalisation of private Oxbridge mentoring by my peers who so often express guilt about their private school privilege (and other varieties on the theme) screams a confusing howl of cognitive dissonance. I almost fear that simply talking about educational privilege without tackling the systemic issue at hand is deemed enough by some to consider themselves off the hook of their own choosing. Also, the university itself has various paid and opportunities for access work during the year, most notably with the university’s UNIQ programme, so you can make the choice to earn a bit of extra money doing work which actually targets students who would otherwise be left out of the private mentoring racket.

In an ideal world, free access to passionate tutors for low-income students does seem optimal, but I am sympathetic to the argument that students deserve to be fairly compensated for their work and sharing their knowledge. After all, if you extrapolate that logic, I certainly don’t expect teachers and university academics to be poorly compensated for their work. In theory the Pupil Premium offered to state schools would be used to support students to provide tutoring, intervention and support, but let’s be real – the state education system in this country is facing more than its fair share of financial shortcomings. Some organisations do charge for tuition in order to subsidise support for less advantaged students, and university students struggling through scant loans and heavy debts can get a decent income from the tutoring. It’s just a shame that the resources of schools are often too lacking to realistically make this business model viable.

I accept that I am perhaps rather more hardline on the issue than most, but access to free, quality education is an important principle to me. It goes beyond complaining about tuition fees when you have to attend ‘Zoom University’. At the end of the day, however, I would feel like an utter hypocrite if I charged people for support when I myself could not have afforded it. Despite my reservations about the university, I do care about access, not pulling the ladder up from behind me.