CW: discussion of mental illness; brief references to child prostitution and fascism.

If you spend time browsing just about any forum or social media platform, you will most definitely be familiar with the concept of “literally me” characters. People (mostly men) will cling to these characters – archetypal, restrained, and intelligent figures who rebel against what they perceive to be society and its norms – because they are relatable. Male characters who play traditional masculine roles in their respective societies but are eventually alienated from the mundaneness of modern life make classic candidates: the Travis Bickles, Patrick Batemans, and Tyler Durdens of cinema. They can come from all types of backgrounds and can take many forms (benign, irreverent, or malevolent) on screen. Yet, “literally me” characters consistently gain a form of supreme social consciousness, usually completing a journey from a life of complete existential emptiness – oftentimes coupled with a debilitating mental illness – into a transformation of true self-affirmation and self-acceptance. This type of character is used to convey criticisms of and social commentary on the human condition and contemporary society, drawing the viewer in with a “hey, I could’ve done that too!” approach.

The much-referenced character representing this archetype – Patrick Bateman from American Psycho (2000) – is a clear example of someone disassociated from a postmodern and hyper-consumerist ‘yuppie’ culture, a direct consequence of Reagan’s economic policies. Bateman has no personal identity but, to paraphrase Jean Baudrillard, is merely a “sign” amongst other signs. He associates with items, consumer goods, and brands – from suits to music and even to the typography of his co-workers’ business cards, which he uses to elevate his social status. This is all symbolic of his own psychosis, as he eventually comes to realise, as well as mass-society psychosis.

“Literally me” films did not begin with American Psycho,but can be traced all the way back to the 1950s with Rebel Without a Cause (1956), which presented a counter-cultural perspective on the dominant, traditional masculinity of post-war America. Following this, Clockwork Orange (1972) and especially Taxi Driver (1976) could be considered grandfathers of this ‘genre’. In the latter, Robert De Niro plays an insomnia-riddled taxi driver, Travis Bickle, who is presented as likely to be suffering from PTSD due to his experiences in the Vietnam War. He witnesses the late ‘70s New York nightlife, driving past criminals, prostitutes, and mentally ill individuals, who he sees as representative of the depravity and degeneracy of the time. These debilitating conditions echo the experiences of writer Paul Schrader, who was plagued by similar pathological loneliness. Eventually, Bickel seeks to exercise all of his pent-up rage in the form of existential, cathartic violence. His routine, after this crisis, mirrors YouTube self-improvement guides: he begins to eat healthily, embraces an exercise routine, and completely stops consuming porn. Yet, his encounter with a child prostitute, played by Jodie Foster, shifts his perspective. For Travis, like all of us, there is a choice to be made: either stare into the abyss and embrace it, or rise above it. Travis seeks to rise above it and save Iris (Jodie Foster’s character) in a manner akin to a reclusive Wild West vigilante-cowboy. From this “literally me” film we can see that, in essence, in order to make the wider world better, we have to make our own world better first:we have to self-improve before we can make a difference in the lives of others.

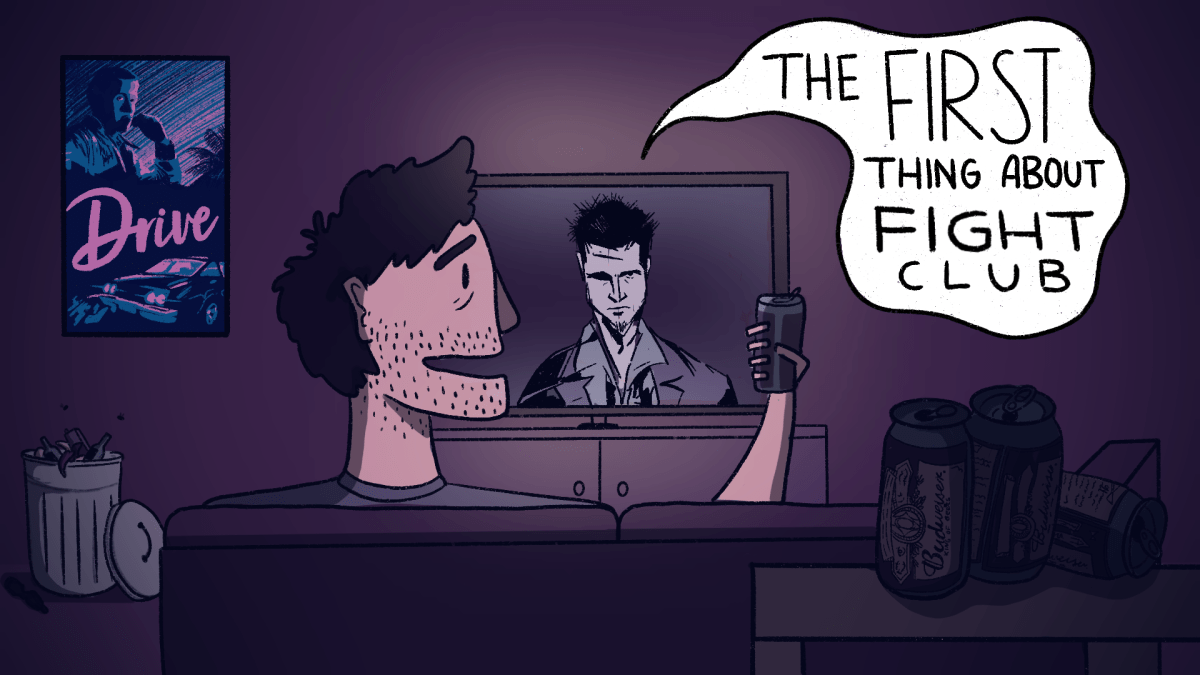

Fight Club (1999) elevated this ‘genre’ to new heights, presenting a well-constructed satire on the fragility of masculinity, as well as American late-stage capitalism. Paralleling Bateman, the unnamed narrator not only experiences a debilitating mental illness, but also lacks any true sense of identity, constructing a thin sense of self through his possessions – his proudly displayed IKEA furniture, his particular brand of Oxford shirts. Once he encounters the esteemed Tyler Durden – a take on Nietzsche’s famous ‘madman’ – this veneer of a postmodern life falls apart. Now, nothing in his once rational life makes sense: he merely lives in a dilapidated house, which is too big and has no reliable sources of electricity or running water. Fight Club (the film and the book) parodies the extremes to which men, who have perceived themselves to have lost their masculinity, can resort: this is the crux of the ‘literally me’ archetype. The crescendo of this parody occurs when our protagonist begins engaging in attacks against the establishment as part of an ‘anarcho-fascist’ terrorist cult, with Tyler as its authoritarian paternal leader.

Fight Club presents a narrative to emotionally-confused young men that Brad Pitt outlines midway through the movie: “self-improvement is masturbation. Now self destruction…” It puts forward the idea that, instead of relentlessly trying to improve oneself to fit society’s expectations, we accept that this is just a superficial rat-race and that the moral cause is to rebel against societal structures propagating the “slave morality of the masses”. Yet, at the same time, we are consistently reminded that the lengths that these men go to rebel against social structures are senseless and impractical: it is crucial to recognise that only objecting to authority in itself is not admirable, but standing up for what one genuinely believes in is.

Another notable “literally me” character can be found in Drive (2011). In the film, Ryan Gosling plays an unnamed, stoic, introverted, and sleek getaway driver who always seems to end up in the wrong place at the wrong time. Against the backdrop of an almost fairytale version of Los Angeles, the unnamed driver comes to realise that his criminal lifestyle is incompatible with the lifestyle of his love interest, Irene (played by Carey Mulligan), and rejects her, hence rejecting his potential for love to protect someone that he really cares about. There is a truly mythical aura surrounding the film, created by its many pastiche elements: its reality seems to be a cinematic tribute to Hollywood of the 1980s. As Ryan Gosling most eloquently said in an interview: “The only way to make sense of this is that this is a guy that’s seen too many movies, and he’s started to confuse his life for a film. He’s lost in the mythology of Hollywood and he’s become an amalgamation of all the characters that he admires.” Much like the unnamed narrator, we, as avid film fans, also take up the traits and personalities of the characters we admire in movies. However, in his rejection of these fantasies and acknowledgement of the real hurt that he is causing, Gosling’s eventually principled and selfless driver rises above the situation that he’s placed in, becoming a moral anti-hero. Instead of being stereotypically united with his love interest at the end of the film, he is forced to accept that he cannot live with her and, ironically, becomes a character that the audience – usually young lonely men – aspire to be like.

Gosling plays another such character within this ‘genre’ as K, the LAPD police officer in Blade Runner 2049 (2017), a highly introverted, bioengineered human in the gruesome profession of hunting, essentially, older versions of himself. The stress of his role causes him to experience severe dissociation with regard to his profession, and he desperately tries to make himself human. K is the definition of a man who doesn’t know who he is, a mere shell. After finding out that a replicant has managed to give birth to a human child, he is forced to investigate the child’s identity, eventually leading him to an investigation of his own potential humanity. In a particularly moving scene, a giant purple Joi, K’s female AI companion, is projected in front of him. After she states that: “You look like a good Joe [K’s human name]”, K quickly and despairingly realises that his whole relationship with Joi (and, by extension, his whole life) is artificial, perhaps even preprogrammed. In this scene, he finally realises his purpose: he figures out that he can do something about the circumstances that he has found himself in. He decides to (re)affirm his humanity by sacrificing himself for a noble cause when he saves Deckard and reunites him with his replicant child, hence giving his own short life some fulfilment and meaning. Despite being manufactured as a machine, he chooses to live and die as a human. Lonely young males’ association with K is symptomatic of the ills of social isolation and the artificiality of modern society. The allegory is clear: it is the alienation from a cold, modern society that drives affiliation to these “literally me” characters.

“Literally me” characters can come from all walks of life, from Wall Street bankers to local mobsters. However, they consistently experience severe mental illness and manage to, oftentimes, subvert baseline societal expectations. They almost always have some form of elevated social and/or psychological conscience. They share some dissatisfaction with the world, something that we all have – but unlike us they do something about it, whether for good or bad. These characters do not lay restless but act as they think they should, defying social norms through some form of cathartic release. As viewers, we associate with them. We are them, yet we do not act as they do.

It does become problematic, however, when viewers make the step from associating with these characters to replicating their (at best) anti-social to (at worst) violently criminal actions.

Patrick Bateman, for example, is a highly narcissistic, hedonistic, and sadistic Wall Street banker, yet some want to be him; it is so common to see people miss the satirical message of these films entirely. Similarly, Fight Club is a clear satire on the ways in which sexually and emotionally frustrated men will self-destruct in order to protect their own fragile masculinities. Yet, in forums online, countless viewers have interpreted this self-destruction as honourable and admirable. The appeal of these interpretations, however, is clear to understand. We want to see ourselves as different from society’s norm. We want some risk and adventure in our banal lives. These “literally me” characters are larger-than-life figures that are willing to bite the bullet, take action and confront death, something which we fantasise about for ourselves.

The social alienation and hyper-commodification that rose from late-stage capitalism can be associated with the removal of identity away from communities towards the market and products. These characters represent a outlet through which emotionally and/or sexually frustrated men can express cathartic pleasure in associating with; their aesthetics, ideals, frustrations with modern society, social and societal apathy and so on. It is not the fault of the writers and philosophers who postulate these ideas and characters, but rather, the attraction of these characters has to do with symptomatic structural problems within our society. Popular media does not only represent a cultural reality but highlights amaterial reality – a reality that explains ‘Literally Me’ characters’ popularity.