The femme fatale is a trope that has long existed in cinema; emerging originally in film noir, it is still gracing the media today. From Basic Instinct to Sherlock’s Irene Adler, she is self-sufficient, strong, seductive. Most importantly, she is dangerous. Despite the common assertion that this character embodies female empowerment, as opposed to the archetypal domestic, demure womanhood that defines her predecessors, I still wonder: is she really a symbol of female empowerment, or a social rejection of it?

When we think of the femme fatale, we see destruction and seduction strutting hand in hand. In the quest for domination over men, her sex appeal is her first and most significant weapon – often her only weapon. This is exactly what makes her character so dangerous, not just to the men in the fictional world she occupies, but to women in real society.

The femme fatale is a hyper-sexualised product of the male gaze, playing on the premise that behind every powerful woman lies a black widow, ready to mate and kill. In its essence, the trope derives from a fear of female sexuality, and its perceived ability to emasculate. This is why the femme fatale’s eroticism is never framed as genuinely empowering; instead, it is created by a man (for the most part), and destined to end in despair.

Look at Alex (Glenn Close) in Fatal Attraction. She has an affair with a married man, becomes obsessive, and tries to destroy his life. Despite clearly needing medical help, her instability is villainised; her suicidal tendencies are framed as manipulation. She is the original ‘bunny boiler’, branded a ‘crazy bitch’, because the minute she no longer caters to a male fantasy, she is undesirable, and thus condemned.

Clearly, the femme fatale’s deviation from the sexual and psychological norm represents a direct threat to the heteronormative, nuclear marriage complex. Alex disrupts the domestic Eden of (sexless, unfaithful) marriage, and so she must die at the hands of the ‘loyal wife’ – her competitor and antithesis. Alex’s downfall ultimately demonstrates a victory for society’s model relationship.

As Kae Tempest writes in their poem Progress, “we’re handed the

Meanwhile, the cheating husband is afforded a happy ending. After all, how was he to know his innocent infidelity would have consequences?

And in the few cases where our femme fatale doesn’t die, the men around her do. Occasionally, she gets to become an antihero, committing murders which are often framed as cathartic triumphs over obtrusive men (for example the throat-slitting of stalker, Desi, in Gone Girl – notably written by a woman). But even within this narrative, the femme fatale eventually settles down with the husband she tried to destroy, choosing domestication over death.

Alternatively, men die as a mere symptom of the femme fatale’s existence – collateral damage for the price of her freedom. In certain iterations of the trope, like Skins’ Effy Stonem or Cruel Intentions’ Kathryn, these women are not murderers, but their entrancing power still brings about the downfall of the men in their life. Whether the woman is framed as a victor, a killer or just a destructive presence, her sexuality destroys everything it touches. Someone always has to die.

We can trace this fear of female sexuality to origins much further back than the film noir genre. Keats and “La Belle Dame sans Merci”; witch trials; tales of Sirens drowning sailors at sea – these are all artistic and historical manifestations of femininity holding power over men, existing in direct opposition to a patriarchal idyll. To look even at the Bible, Eve committed the Original Sin. From the start, disobedient or powerful women have been portrayed as plagues

This creates a them or us dynamic: survival of the most compliant. Whether it is between men and women, or rather two antithetical female tropes, we are pitted against each other in a game of moral natural selection. Yet what invariably remains at the core of the ‘femme fatale trope’ is the vilification of empowered women, and the promotion of their castrated domestication.

While not every dangerous female character is entirely based on misogyny, we must consider whether the killer in question is truly rounded, as in the case of Killing Eve’s Villanelle, or whether she is an exploitation of female sexuality, providing a scapegoat for all of society’s problems. It’s time to abandon the lazy writing that always leaves the femme fatale to blame, and point the finger towards a world which filters women into two categories – loyal wife or evil mistress, Madonna or whore, woman or witch. Let the femme fatale die her fated death one last time, and let a new character emerge whose sexuality is not a sin, and whose weapons come with agency.

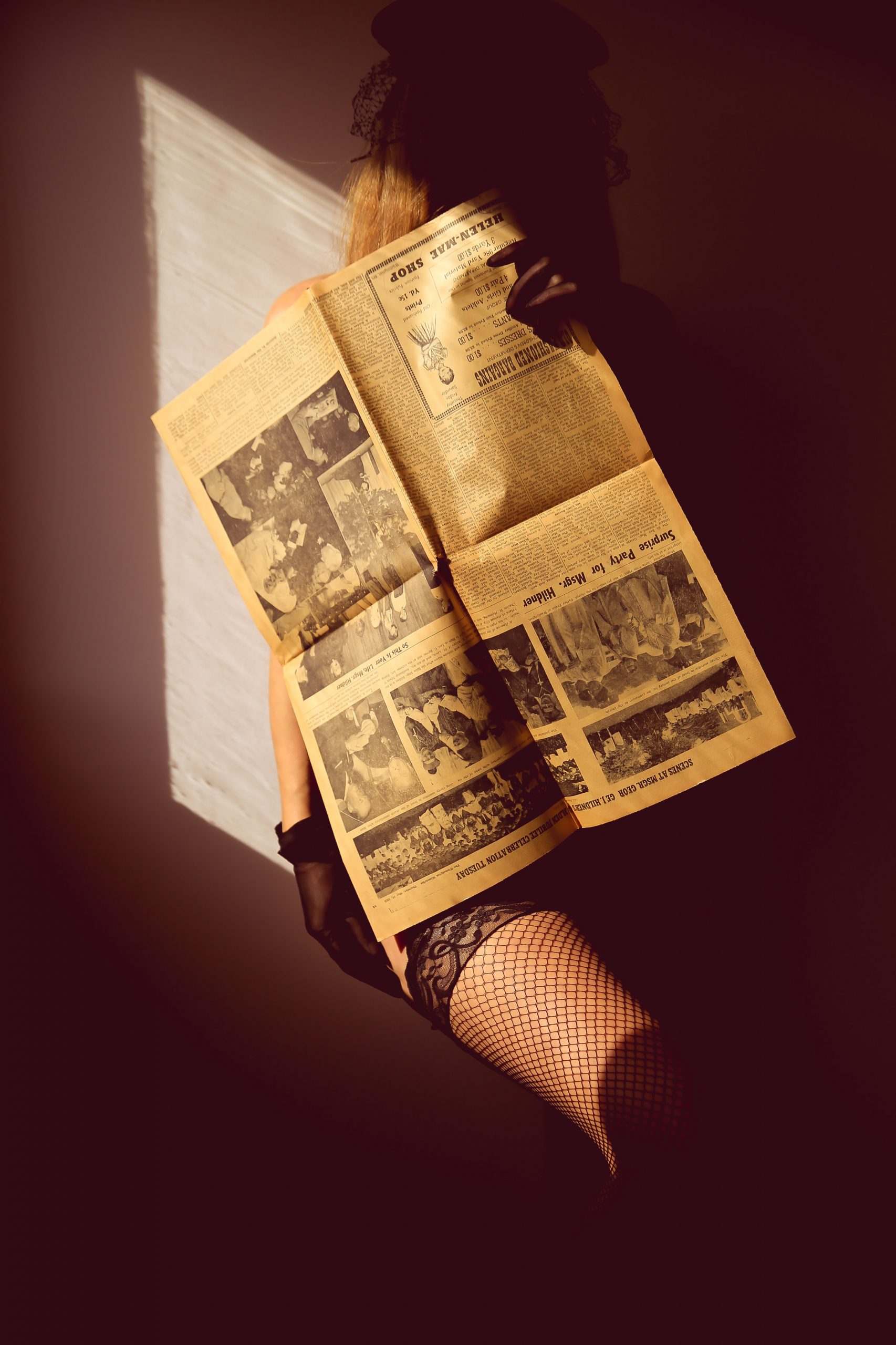

Cover photo: Ava Sol on Unsplash