A note from the editor

In our second edition of It’s the Economy, Stupid, the Global Affairs team takes a look at the biggest economics, business, and technology stories across the world. This week, we look at Turkey’s possible return to economic sanity, the UK’s sloppy statistic reporting, JPMorgan’s commanding lead over other banks, and the new discoveries on the age of the Moon. Also look out for Oxford Women in Finance’s upcoming event looking deeper into JPMorgan!

The Global Affairs section is actively looking for writers on science, technology, economics, and business. No experience necessary, we just want people with the interest to talk about these important developments across the world.

If you’d like to find out more or have suggestions for stories to cover, get in touch at either at david.yang@wadham.ox.ac.uk, or on Facebook!

Erdogan’s Turkey signals return to economic orthodoxy

David Yang

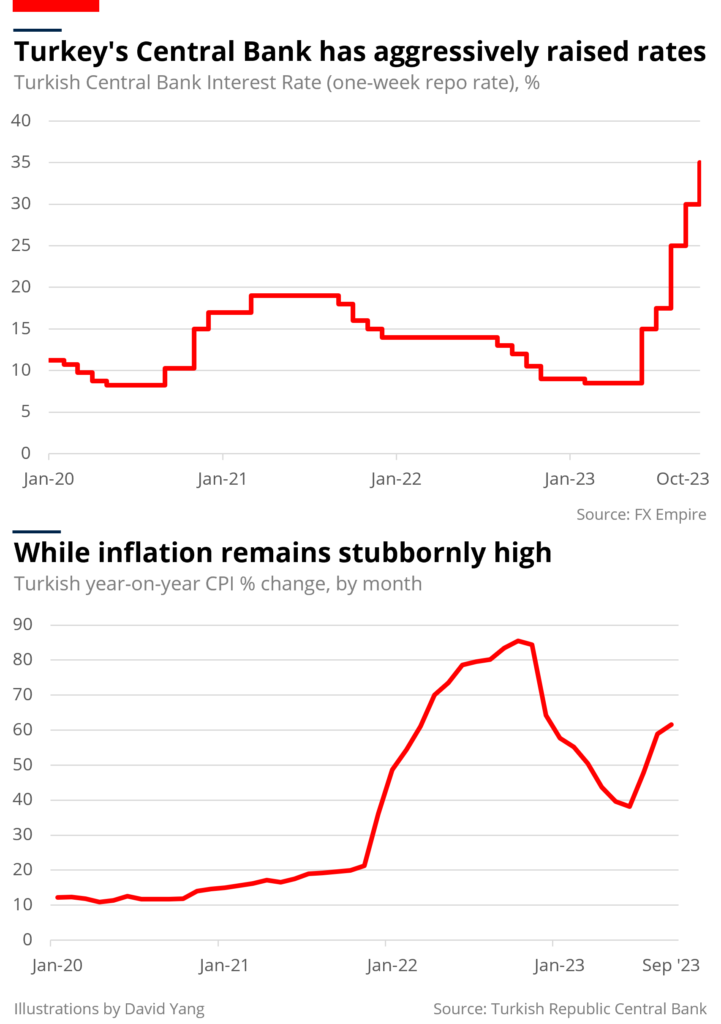

Turkey’s Central Bank has continued its campaign to tame sky-high inflation, raising interest rates by five basis points to 35 percent, the fifth consecutive month of rate hikes. The interest rate rises began following President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s re-election in May of this year, after he won the presidency by his narrowest margin yet in a campaign dominated by concerns over the economy. With inflation at an eye-watering 61.53 percent and not slowing down, helped in no part by generous subsidies and easy money provided by Erdogan in the run-up to the election, Turkish consumers and firms are increasingly being squeezed by skyrocketing price rises.

Erdogan’s infamously unorthodox views on monetary policy, that lower interest rates decrease inflation, have long troubled investors, with the Turkish lira plummeting in value as foreign investors withdraw their money from the country. Erdogan’s beliefs are rightly derided, as it is economically untrue that lower rates lower inflation. Lower interest rates actually increase inflation, and Erdogan’s imposition of low rates is to blame for Turkey’s economic crisis.

To calm investors, and once it became politically convenient after the election, Erdogan appointed two market-sympathetic officials. Mehmet Simsek, a former senior economist at Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank, made a return to Erdogan’s cabinet as Finance Minister. Simsek had helped Erdogan’s government navigate the post-2008 recovery, before being replaced by Erdogan’s son-in-law in 2018. Simsek announced that Turkey would return to “rational ground”, and has so far unveiled a raft of pro-market policies. Hafize Gaye Erkan, a Harvard Business School alumnus and former a managing director at Goldman Sachs, was appointed governor of Turkey’s Central Bank, and has since shown her commitment to monetary orthodoxy by continually raising interest rates, though she may be falling short of investors’ demands.

As interest rates rise, stock prices have plummeted and economic growth looks likely to slow, which might shock a country so used to cheap loans and easy credit. Two questions still hang uncertain over Turkish consumers and foreign investors. First, if Erdogan can stamp out inflation at all; and second, if he is willing to inflict the economic pain necessary to do so.

Where to draw the line? UK Statistics are becoming a joke.

Ollie Edwardes

I get it: stats are boring. Yet the UK statistics agency is doing its best to add some spice to the mix.

Having reliable official statistics matters. Without them the big decisions by government ministers and independent authorities, such as the Bank of England, will be based on false information and likely turn out to be wrong in hindsight. Sadly, a series of recent announcements from the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) have cast serious doubt on the validity of key UK data points, such as GDP estimates and unemployment levels.

The public and ministers need to draw a line somewhere, and it’s not unjustified to be a little bit mean (an average joke, I know). The issues behind all this need to be fixed asap, but until that happens I’d take any recent or upcoming data with a large pinch of salt.

Statistics are the foundations of good policy.

The public, their elected politicians, and those chosen to run autonomous organisations – like industry regulators – rely on good information in order to make their decisions. Researchers use official statistics when conducting their analysis, such as the wave of literature being published on the UK’s economic response to the pandemic and businesses rely on them to make investment decisions. Furthermore trustworthy stats are a sign of strong institutions more generally, which would make the UK a more appealing destination for businesses and investors.

The ONS is not doing its job on employment statistics.

Take (un)employment data, for example. It’s a useful collection of stats, which are widely reported whenever the new numbers are released and voters can rightly use this to gauge how well politicians are managing the economy. The Bank of England rely heavily on this data when making their economic models and setting interest rates (broadly high unemployment means the economy is operating at under capacity, whereas low unemployment means the economy is at a stretched capacity).

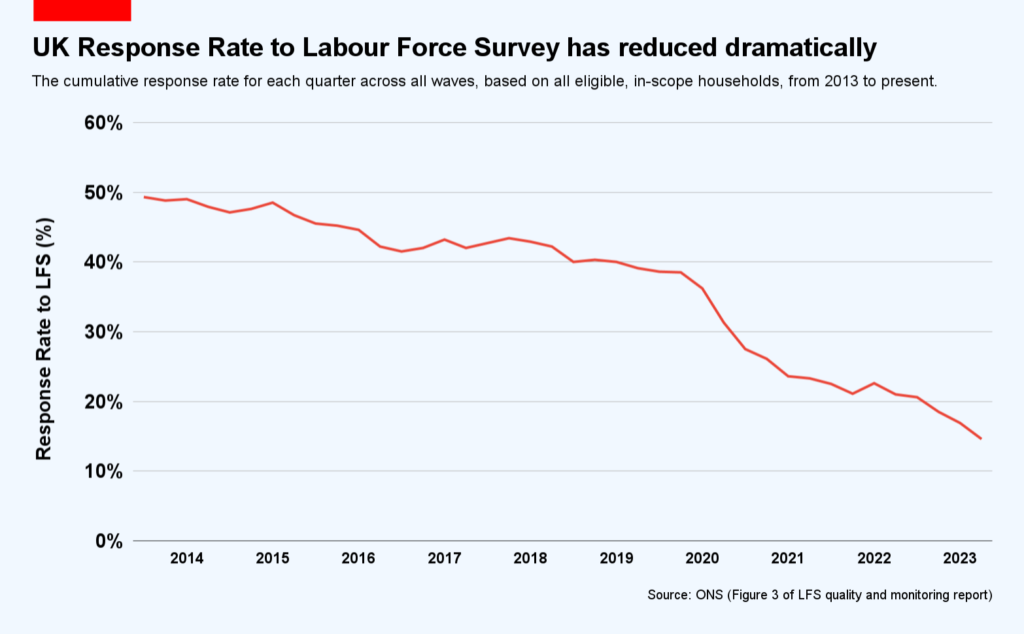

The ONS actually estimates this by conducting a survey of tens of thousands of households across the country, and publishing all the stats about how many people are working, how many hours, and in which parts of the country. Disappointingly, the response rate to this survey has fallen dramatically (down to 14.6%), so much so the ONS stripped the figures of the national statistics branding last week. Instead the figures – released last week after being delayed – were branded as experimental data.

This is because they are based on tax and benefit records instead of the usual survey. By making this change the figures are automatically difficult to compare to previous releases, because they use a completely different methodology.

As you can see from the graph this problem has been brewing for a long time, but the ONS has failed to do anything about it. Even last week they seemed unwaveringly upbeat about their methods and published this blog post about making their labour market statistics fit for the 21st century (only 23 years late to the party). At least they appear to be making changes, but they’ve left it far too late.

The Bank of England will announce its latest interest rate decision on Thursday (2nd November) alongside the latest monetary policy report and its updated forecasts. Only, this time around, their economic forecasts are based on dodgy figures and their decision may turn out to be wrong.

GDP revisions are bad too.

The problems are not just in unemployment figures. In September the ONS revised its previous GDP figures and found that cumulatively the UK is now £50bn better off than it thought. Previously, the statistics agency estimated that GDP in Q2 (April, May & June) 2023 was 0.2% below its Q4 2019 level; it now thinks that the economy actually grew by 1.8% over that time. Sector by sector the data was even worse, with basic iron and steel manufacturing increasing by 56 per cent between 2019 and the end of 2021, according to the previous figures. The update changed that to a 66 per cent decline.

Ultimately, there are clearly some big flaws in the approach of the Office for National Statistics and the country needs this to change. It’s clear that they are adjusting some of their methods, but the organisation would also benefit from more money. They are a small and cheap government department, which has had to take on a lot more work since the UK left the European Union and it is also struggling to recruit staff. A little bit of money (genuinely insignificant amounts in terms of UK tax and spend) might go a long way.

JPMorgan leads the pack of Big Banks

Alice Grant | If you’d like to hear more about JPMorgan, check out Oxford Women in Finance’s upcoming event tomorrow, more below!

With profits rising 35% just two weeks ago, JPMorgan, one of America’s largest investment banks, is evidently doing well; with interest revenue margins substantially increasing from this time last year. Though the high interest rates in the US and in the UK are a concern for much of the financial world, the largest Wall Street players seem to be immune as higher rates mean higher profit.

It may have come as a surprise then, when the news recently broke that Jamie Dimon is to sell one million of his JPMorgan Shares in 2024, reducing his stake in the bank for the first time ever – a generally unprecedented move for Wall Street executives.

Due to it being highly uncommon for senior managers to sell their shares of the banks which they oversee, speculation naturally arose as to 65-year old Dimon’s intention of continuing his role as chief executive. JPMorgan’s press team were quick to insist that the sale was purely from personal motives which include diversification and tax-planning.

Though such a move would usually point to a lack of confidence in the corporation, not only do the recent statistics suggest otherwise, but Dimon’s stake in the bank remains significantly large. The Financial Times, reporting on JPMorgan’s success under Dimon, have pointed out that shares have witnessed a rise of 250% since he first took on the role in 2005. Interestingly, Dimon not only bought a sizable amount of his shares in 2016, but was also awarded 2 million stock in 2021 as a reward from JPMorgan’s board – an illustration of the power wielded by these banks in enriching long-term employees.

Gloomy Forecasts

Dimon has also been making headlines for recently drawing attention to the difficulties the markets will face as the Israel–Palestine conflict escalates. The chief executive has been quoted in multiple media outlets saying that this is the “most dangerous time the world has seen in decades.”

But to what extent will the geopolitical situation affect the big American banks, like JPMorgan? There are mixed views. The expressions of concern reaching tabloids clearly point to some anxiety over both Ukraine and Gaza wars, though as for now, it’s business as usual.

For the eurozone, however, JPMorgan predicts a foreboding stance; the bank recently forecasted the euro dropping to fall to parity with the rate of the dollar by the end of 2023. This is linked to the driving up of energy prices due to the Gaza war and the fragile international climate.

JPMorgan’s Ina De coming to Oxford

For those interested in learning more about JPMorgan’s work, the Oxford Finance Society, in collaboration with Oxford Women in Finance, will be hosting Ina De on Thursday 2nd November.

As the co-head of JPMorgan’s Strategic Investors and Financial Sponsors Group in Europe, Ina De has been at the forefront of ensuring JPMorgan retains its renowned success amongst investment banks over the past four years.

De promises to reveal strategies and insights she has learned over her long-spanning career as well as her own unique perspective on the current global markets. As someone who has spent years as part of the Financial Sponsorship Group, not only will her insights on business and transactional work be fascinating, but it will be beneficial to hear about the challenges she has personally encountered.

Details for the event can be found on the Oxford Women in Finance website.

The Moon found to be older than previously thought

Krishh Chaturvedi

The Earth and the Moon have a complicated intertwined history, with common origins dating back to soon after the formation of the solar system. About a 100 million years after the solar system and planets formed, it is believed a Mars-sized body struck the infant moonless Earth, ejecting a large mass of material that eventually became the Moon. The energy involved in the impact meant its surface was initially molten, but as the lunar magma ocean cooled, the material solidified.

This was originally thought to have occurred 4.42 billion years ago, an estimate developed based on modelling and analysis of lunar samples. However, it has been tricky to find a definitive age. Researchers now suggest the Moon could be 400 million years older than the estimate previously agreed upon, as a result of new analytical techniques being applied on lunar samples brought back in 1972 during the Apollo missions.

The technique used, described in the study published in Geochemical Perspectives Letters last week, analyses a crystal of zircon, one of the oldest minerals to survive from the Moon’s formation. It looks at isotopes of uranium and lead present in the crystal, as uranium decays into lead radioactively with a predictable rate. Thus, by analysing the amounts of lead and uranium we can estimate the time that has passed since the zircons solidified from molten material.

The study has been accepted favourably by the scientific community, with researchers agreeing that this fits more comprehensively with timelines of other events such as formation of distinct layers in the Moon’s interior. The better understanding of the Moon’s age will help scientists model its evolution too. Having a confirmed starting point is useful to better understand the processes and composition of the Moon now, and predict its future behaviour. Furthermore, it also gives a better understanding of the Earth’s history since the lack of tectonic activity on the Moon better preserves its history.