In 1923, after four hard-fought years of fending off foreign invaders, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk founded the Republic of Turkey as an independent, sovereign state. Still revered throughout Turkey today, the nation’s founding father had a grand vision for his country: to turn it into a modern, secular, and democratic nation-state.

In the 100 years since, Turkey has endured a turbulent history, experiencing economic crises and military coups. Yet Ataturk’s goals in many ways succeeded. Often an odd one out in its neighbourhood, military coups never failed to swiftly return power to democratic civilian government, which has allowed Turkey to maintain one of the Middle East’s most stable and functional democracies. Written into the constitution is a commitment to secularism in public life, an oddity among majority Muslim countries. Since 1952 Turkey has been an important member of NATO, the Western military alliance, while other Middle Eastern countries maintain tenuous, if not outright hostile relations with the West.

As the nation approaches its centenary, Turks prepare themselves for a pivotal election. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has ruled the country as prime minister and then president for 20 years, is a divisive figure. To his supporters, he has improved living standards, restored Islam’s importance in society, and forged Turkey’s place on the world stage. To his critics, he is a dangerous strongman who has centralised power around himself, eroded the state’s institutions, wrecked the economy through nepotism and incompetence, and built a cult of personality through handouts and corruption.

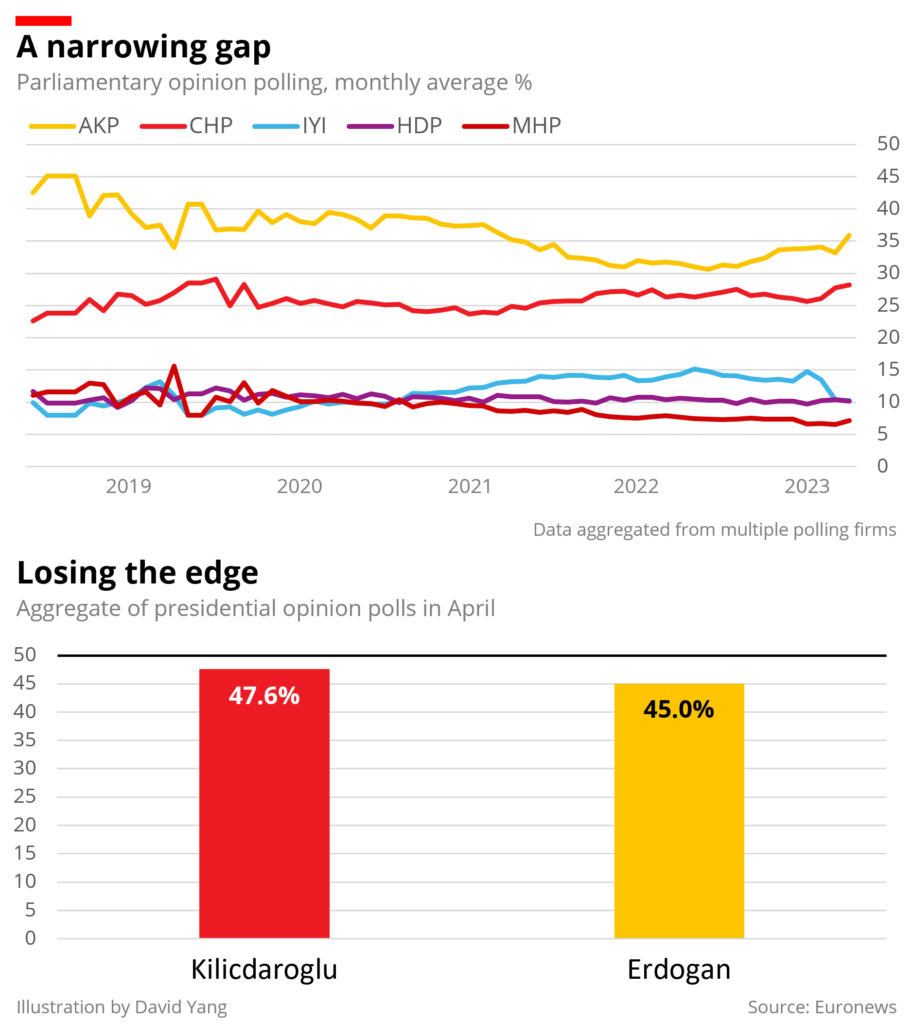

A charismatic populist, Erdogan has won every national election since coming to power. But as his polling wallows at historic lows, many see the presidential and parliamentary elections scheduled for May 14 as a rare opportunity to finally oust Erdogan and his religious-conservative Justice and Development Party (AKP) from government.

A waning nation

Today, the Turkish economy is in disarray. Inflation has skyrocketed to over 50 percent, the current account deficit is at a record $9.85 billion, and the value of the Turkish lira has plummeted. Any economist would advise that the central bank raise interest rates to tame inflation and prop up the currency. Yet President Erdogan has stubbornly adhered to his mistaken theory that lowering interest rates help reduce inflation. Low rates make money cheaper, stimulating economic growth. Still, wages fail to keep up as prices rise at such incredulous rates.

Erdogan’s obstinance may not have been so damaging had he not consolidated so much power around himself. Unlike central banks across the developed world, the Central Bank of Turkey has no real independence. Instead of economists and technocrats making careful decisions, Erdogan controls nearly all of the state’s institutions via appointed relatives and friends. Erdogan’s son-in-law Berat Albayrak failed to tame a turbulent currency crisis as finance minister. When his replacement disagreed with Erdogan’s economic policy, he was swiftly replaced by Erdogan’s close friend Nureddin Nebati. Interest rates were slashed and foreign currency reserves sold off to prop up the lira. Erdogan’s nepotism infests all levels of Turkish state and society, from exempting his son from tax via Turkish Youth Foundation board membership, to doling out tax breaks to another son-in-law’s defence company.

Such control was only made possible by Erdogan’s constitutional referendum, which granted him sweeping powers and weakened parliament. In the aftermath of the failed military coup of 2016, Erdogan used the atmosphere of fear and uncertainty to get the people to grant him greater executive power. With it, he has silenced journalists and reined in the media, of which 90 percent is estimated to be under his control.

Things were not always so dismal. In 2002, Erdogan and his party were swept to power off the back of widespread anger towards a political establishment and an economic crisis it had brought about. The flurry of reforms his government enacted created a boom and modernised the Turkish economy for the 21st century. Inflation was tamed after decades of double-digit figures. Foreign investment poured into Turkey, with $240 billion entering the country between 2002 and 2021, compared to just $14 billion in the twenty years before. Female participation in the workforce rose from 23 percent in 2004 to 35 percent in 2022.

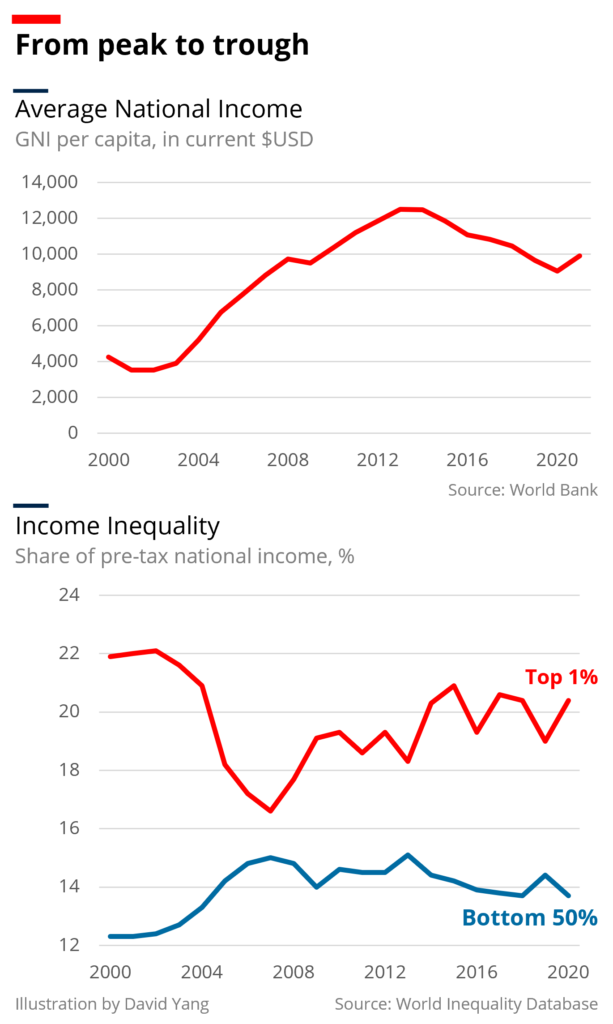

But while Turkey has come a long way, these strides in development are being lost. From 2002 to 2014, average national income per head more than tripled, but after 2015 nearly all gains since the 2008 recession were wiped out. Similarly, the income gap between the top 1 percent and bottom 50 percent narrowed until 2007, after which it began steadily rising. High inflation and handouts to friendly businesses have squeezed the poor while buoying Erdogan’s wealthy associates. 20 years ago, Erdogan came in on promises of eliminating corruption, inequality, and an economic crisis. 20 years on, his government stands accused of the same sins.

A united front

For all of Erdogan’s failings, Turkey’s diverse opposition still has a difficult task ahead of them. One of their greatest challenges will be overcoming their own divisions. United in their shared commitment to restoring the parliamentary system and opposition to Erdogan himself, a disparate group of parties formed the Nation Alliance after the 2017 constitutional referendum granted President Erdogan sweeping executive powers at the cost of parliament. The diverse coalition of parties varies in ideology and age. The centre-left Republican People’s Party (CHP) is the largest and oldest, dating back to the founding of the Turkish Republic. The centre-right IYI party (Turkish for “good”) was formed just in 2017, splitting from Erdogan’s far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) allies after they supported his referendum. Smaller members include two parties formed by a former economy minister and a former prime minister that left Erdogan’s AKP, moderate conservatives, and Islamists.

Seeing mild improvements as an alliance in the 2018 general election and surprise success in the 2019 local elections, the Nation Alliance has tightened ranks, launching a joint manifesto. In it, they pledged to undo Erdogan’s legacy: a restoration of the parliamentary system, to purge corruption in state institutions, and to strengthen the independence of the central bank, courts, and electoral commission. The opposition believes that taking away the president’s influence will end what they see as Erdogan’s deluded monetary policy. The alliance remains committed to rolling back Erdogan’s islamisation of Turkey. But to soften perceptions of the CHP’s historic hard-line secularism and to attract more of the AKP’s religious voters, the manifesto promises to enshrine a woman’s right to wear a headscarf into law.

Yet cracks have shown in the opposition. On top of their disparate ideologies, personalities have gotten in the way. The “Table of Six”, as the leaders of the member parties are known, only announced their joint presidential candidate in March, just over two months before the election. Kemal Kilicdaroglu, leader of the CHP, received the approval of five of the six parties. However, IYI leader Meral Aksener left the alliance in protest. Citing better polling for the CHP mayors of Istanbul, Ekrem Imamoglu; and of Ankara, Mansur Yavas, Aksener demanded that either of them be the presidential candidate. Only after a public spat and concession to nominate the mayors as vice presidential candidates did IYI return, highlighting the group’s divisions.

Notably missing from the Nation Alliance is the pro-Kurdish left-wing People’s Democratic Party (HDP), who instead lead their own smaller leftist alliance. IYI’s nationalist tendencies led it to rule out any cooperation with the HDP, which the Turkish government accuses of being associated with the PKK, a Kurdish terrorist group. However, Kurds make up 18 percent of Turkey’s population, and the HDP won 8.4 percent of the vote in the 2018 presidential election, which could tip the scales in such a tight race. To the relief of the Nation Alliance, the HDP announced in March that it would not field a presidential candidate, and in April officially backed Kilicdaroglu. Kilicdaroglu’s status as an Alevi Kurd has gained him sympathy from Kurdish voters. As vice presidential candidates, the popular mayors Imamoglu and Yavas will bring more nationalist Turks into the fold. With the near-united opposition, Erdogan faces off his most challenging election yet.

The Republic at a crossroads

For 20 years Erdogan’s party has won every national election, yet this May will be his toughest one. Although his great charisma, oratory skills, and Islamic rhetoric have won him a devoted base among religious conservatives, Erdogan knows winning an election takes more than a silver tongue. Utilising his control over the state’s institutions and the media, Erdogan has done everything he can to crack down on opposition. Through his connections to, and control over much of the media, he has amplified his platform while cutting off favourable opposition coverage. Via the courts, the Kurdish HDP has been under a media ban since 2017, with Erdogan intending to ban the party outright, while independent international media outlets have been shuttered.

Most astonishingly, Erdogan handed popular CHP Istanbul mayor Ekrem Imamoglu a two-year prison sentence and ban from politics over criticising the Supreme Election Council. In the 2019 local elections, Imamoglu ousted the AKP from the Istanbul mayorship in a major upset for Erdogan, where he once held the position. Erdogan demanded a re-run, in which Imamoglu won by even more. After his second win, Imamoglu reportedly referred to those who cancelled his first result as “idiots”, which has been used over three years later to convict him. Though his sentence and ban are not enforced while the case is appealed, the move is indicative of the lengths Erdogan is willing to go to avoid defeat.

Erdogan has also increasingly used government handouts to buy votes, unleashing a massive last-ditch spending campaign to alleviate the worst of the economic crisis. He has hiked the minimum wage by 94 percent, beating inflation; scrapped the retirement age, allowing two million Turkish workers to retire immediately; offered cheap loans for first-time buyers; and extended tax debt relief to millions. It is speculated Erdogan’s calling of early elections in May was so that these handouts don’t lose their value from sky-high inflation, especially as voters overwhelmingly rank the economy as the most important election issue.

Yet what may end up being Erdogan’s undoing was something no one could predict: the tragic earthquakes that devastated swathes of southern Turkey. The government has received not just criticism from the opposition, but also the ire of citizens impacted by the disaster. From a botched rescue effort to Erdogan’s 2018 amnesty for buildings that failed to meet safety regulations, thereby causing so many buildings to collapse, the Turkish people are outraged at the government’s incompetence. The anger has even spread to football stadiums, where Erdogan supporters tend to coalesce. Striking scenes of spectators throwing thousands of toys in support of impacted children and chants of “government resign” have rocked Erdogan’s support. With the AKP polling at historic lows and a slew of polls showing Kilicdaroglu with a sizeable lead over Erdogan for president, Erdogan’s position has never been more tenuous.

As Turkey prepares to celebrate the centenary of its founding this year, it must reckon with its most consequential leader since Ataturk himself. Beyond just selecting their president, the Turkish people face a pivotal choice. One between an autocratic presidency or a parliamentary democracy; between a more Islamic or secular country; between rejecting or embracing Ataturk’s vision for his republic. The past 20 years have culminated in a battle for the soul of a nation—one which, in Ataturk’s vision, can only be won at the ballot box.