Illustration by Isabella Diaz Pascual

Never Have I Ever is a Netflix series that falls under the category of ‘Comedy’ as well as ‘Drama’. And it’s true: Devi Vishwakumar’s navigation of her high school and her love life is, in my opinion, the best possible way to demonstrate what ‘chaotic good’ (or ‘chaotic evil,’ depending on the episode) is. But, the series doesn’t shy away from handling other topics that are just as natural a part of life as romance is for teens: sex, sexuality, immigrant culture, and – above all – grief.

Over the course of three seasons, we follow Devi in the aftermath of her father’s sudden death. From the get-go I was in floods of tears. Some nine years ago, my father also died a – what seemed to me at the time – sudden death. I was not in high school, but just like Devi, I to this day have still never quite recovered from how abrupt it seemed, despite my father’s long illness and hidden battle with Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma.

Whenever Never Have I Ever focuses on Devi’s point of view, John McEnroe is narrating. I sobbed some more. In a rather fortuitous, and sometimes devastating, coincidence, both my father and Devi’s were tennis aficionados. True, my father never got around to purchasing McEnroe’s wooden racket from eBay, but maybe he would have if given the chance. My father used to be a tennis coach. He would to talk to me about McEnroe; he twice won gold at the British Transplant Games in tennis.

Nevertheless, it was more than these surface-level similarities that I identified with. Devi’s grieving process is what hurt the most: watching her be completely blindsided with it as I am. Getting caught off guard because you’re sure you’ve caught a glimpse of him in the audience or a face in the crowd walking down the street. Running to the toilets and crouching on the floor to try and ease the pain, fear and suffocation of a panic attack. Feeling guilty when you realise that you’re starting to be happy again instead of drowning in grief. Feeling awful for living your life.

Completely forgetting about a past relic only to suddenly come across it and burst into tears. For Devi, it was McEnroe’s racket and its violent resurfacing in her life. For me, I was clearing out my room and found the birthday cards he had written to me as a child that I didn’t remember receiving. Or rummaging through a wardrobe and finding all of his Transplant Games medals inside a bag. I still can’t bear to take out his tennis racket.

The mother of Devi’s boyfriend describes her panic attack as “hysterical”, saying that she has “too many problems”. So when I then heard Devi ask “What if nobody ever loves me because I’m always too much?”, my heart broke: both for my 12-year-old and 21-year-old self. I’ve asked myself this question too. When I first considered writing this article I thought that I was overdoing it by bringing up my father’s death again. That maybe after nine years, I’ve Iost the right to feel this upset by an event almost half-my-life ago. That maybe I’m overdoing it now. And that I am too much. And that I should just shut up.

I’ve had the experience of people in friendships or relationships being unable to support you or comfort you when you’re going through a low spell due to grief. Where, whether intentionally or not, you end up feeling like you are too much because you’re imposing on them.

It’s taken me nine years to realise that this is a lie.

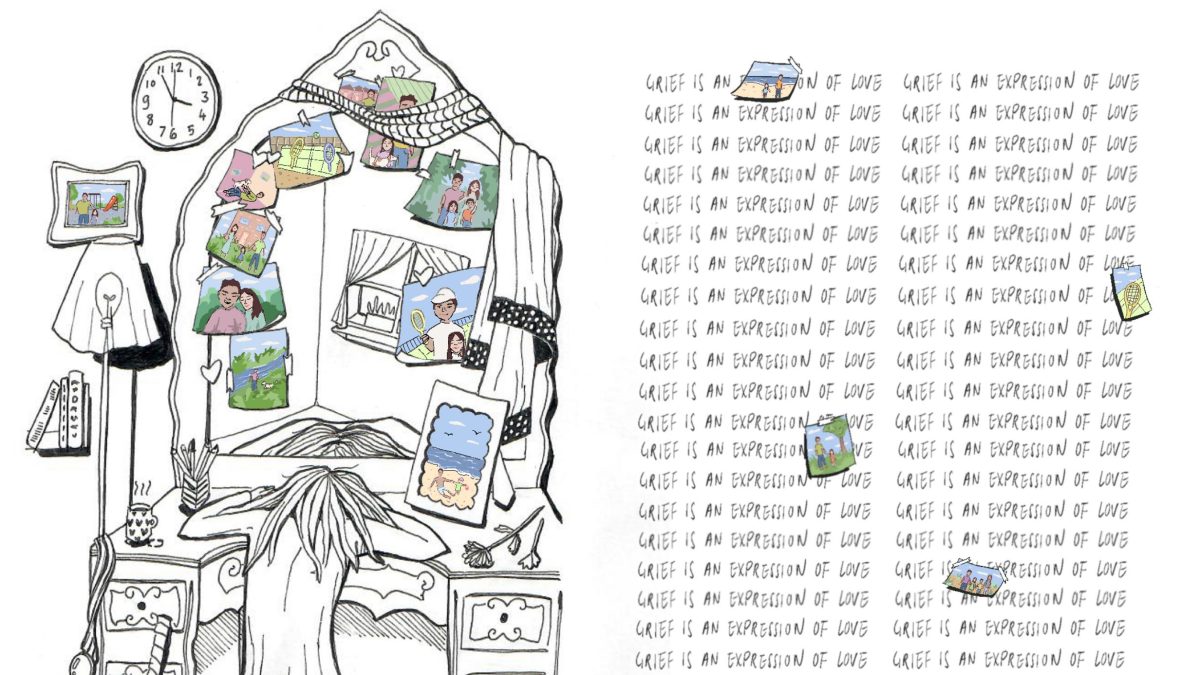

Certain scenes felt bittersweet. Seeing Devi’s photos with her father as a teen pinned to her mirror was tough for a myriad of reasons. There was an undeniable stab of jealousy that Devi got more time and more memories with her father than I got with mine, that he got to see her as a teen whereas my father didn’t. There was the pain of knowing I’m still not at the point where I can look at pictures of me with him and not break down.

The slow-mo shot of Devi’s classmate’s dad hugging him at graduation was another painful moment. The waterworks started up again. In seeing other families’ dads be there for those milestones, those life-changing moments, you’re brutally reminded that you will never have that. Yours will never be there.

Perhaps I’ve deviated a bit from the point I wanted to make, but watching Devi grieve helped me grieve.

There are six words from the series that still ring true:

“Grief is an expression of love.”

Just because I’ve forgotten the sound of my father’s voice, it doesn’t mean I love him any less. Just because my memories of him aren’t always as golden and positive as Devi’s are of her father, it doesn’t mean I love him any less. Just because I’ve forgotten so much of him, it doesn’t mean I love him any less.

I hate with all my heart that writing this article still has me second-guessing whether I have the right to be addressing a single event that happened one September on a Wednesday afternoon. And I hate how reading back my words of trying to be vulnerable makes them sound false and untrue. And I hate that I feel the need to justify my grief.

All I really want to say, I guess, is that in between the laughs and cringes of Never Have I Ever is a girl grieving for her dad. And I’m writing this article because watching it helped me grieve mine. Most of all, I hope nobody reading this has experienced something similar. But if anyone who has is reading this, I hope that you watch this series, laugh a bit, cry a bit, and feel a little bit better.