In many ways, the UK’s economic problems are not unusual. Paradoxically in macroeconomics, the presence of abnormalities is quite normal, and the occurrence of the unexpected has to be expected. The frequent work of economists is to develop models which can describe what happens when an economy is hit by a sudden, one-off shock. In this case the one-off shock was Russia invading Ukraine; this, and the sanctions that followed, caused a sudden rise in the prices of many commodities, including oil and foodstuffs. Yet, the predictability of everything the UK has suffered in the 17 months since Russia’s invasion is agonising. Bluntly, the Bank of England has been too loose with its monetary policy, and the UK economy has suffered as a result.

The job of the Bank of England (BoE) is to use the levers of monetary policy to keep inflation as close as possible to the target rate of 2% per year. But this is not possible in perpetuity, and so dealing with sudden external shocks (or exogenous changes, as economists like to call them) resulting in inflationary or deflationary pressures is a major focus of macroeconomics.

If the Bank doesn’t change interest rates or other aspects of monetary policy following an inflationary shock, then prices will continue to rise faster than desired. This is due to wage-price spirals (when workers demand higher wages because of price rises, leading to further price rises), and their equally potent, though little-discussed, sibling, the price-price spiral (where firms raise their prices because the prices of their inputs go up). Crucially, both firms and individuals set their expectations about future inflation based on current inflation and, like a Delphic prophecy, this guides their every decision, causing subsequent rounds of spiralling inflation long after the initial problem has passed.

The main tool which the Bank uses to control inflation is interest rates. Theoretically, a rise in interest rates reduces inflation because it encourages people to save more and borrow less, reducing in turn the amount of money being spent in the economy. Still, this process is complicated by what is known as the transmission lag, the (estimated) one or two years it takes for rate changes to have a significant effect on the economy. Furthermore, rate rises are never expected to eradicate inflation in one fell swoop. Rather, price rises are imagined to return gradually to target, initially in big chunks, but then in smaller increments in a process lasting several years.

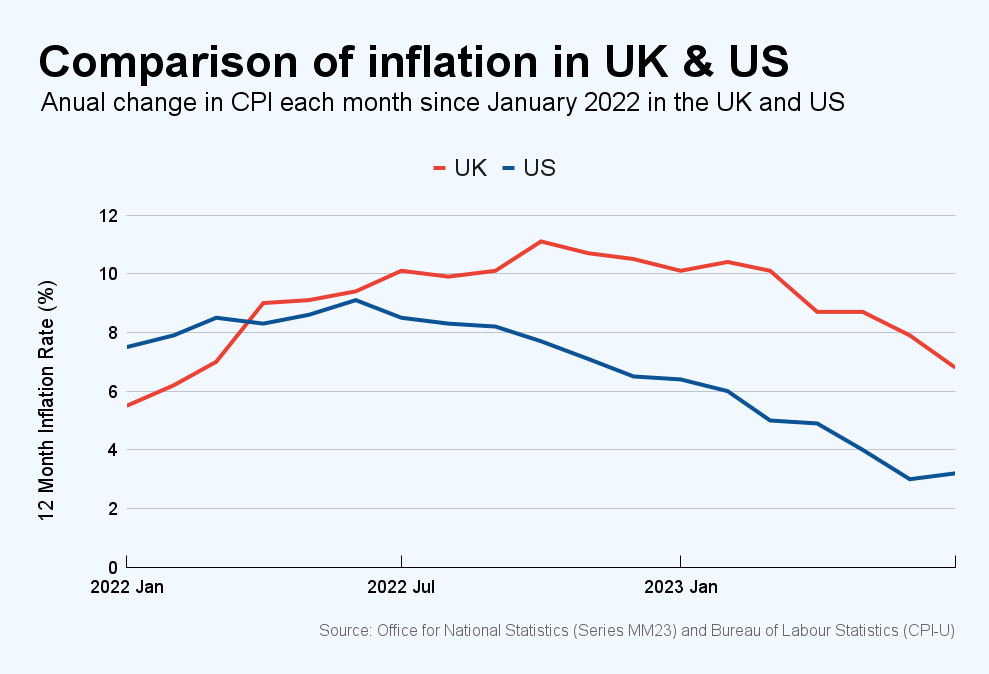

So, 17 months after Russia first invaded Ukraine, you would expect the Bank of England’s initial rate rises (from 0.1% at the end of 2021 to 5.25% today) to be having a marked effect and to see inflation falling rapidly. Instead inflation remains significantly above target and significantly above its peers, as the chart highlights. How has this been allowed to happen?

Well, as Louis Ashworth wrote in the FT, “Bank officials have steered the UK through an inflationary shock driven by factors beyond their control and into an inflationary shock increasingly driven by factors within their control.”

The characters involved with this saga are almost cartoonish. There’s the timid central bank governor, Andrew Bailey, burying his head in the sand, hoping everything clears up soon (like Homer at the nuclear plant), and the tragic figure of Liz Truss, whose hubris only made things worse (more on that later).

Of course, inflation was above target even before Russia invaded Ukraine, but the BoE was rightly cautious during this period, since the factors causing it were largely pandemic-related. The labour market was tight, meaning demand for workers outstripped supply, due to big rises in long-term sickness and early retirements. Global supply chains were also tight due to enduring restrictions around the world. It would have been wrong to overreact at this point, since these problems could well have corrected themselves as restrictions eased and people went back to work.

However, once Russia invaded Ukraine, it became clear that there was a global problem with inflation. Following such a one-off global shock with local effects in the UK, the textbook response would have been a sudden and substantial increase in interest rates. Instead the BoE opted for modest adjustments spread throughout the last 16 months (the largest single rise was 0.75% and that didn’t occur until November 2022). Textbook analysis reveals that such a timid response is punished in the following period as inflation remains higher for longer; and this is exactly what has happened so far.

Of course some would argue against raising rates too quickly, because it could cause a recession, but this is a false economy, since allowing inflation to become embedded necessitates higher interest rates over a longer time period which ultimately keeps GDP lower for longer and only exacerbates problems for mortgage holders.

In addition to rate hikes, the BoE theoretically has one more tool to fight inflation, or would have were it not for Liz Truss’s recklessness.

During the 2008 recession and again during the pandemic, the Bank created new money electronically and used it to buy up financial assets in a process that became known as Quantitative Easing. This was to avoid deflation and curb some of the effects of each recession by pumping additional money into the financial system and encouraging more lending.

In mid-2022 the BoE announced they would begin to sell these assets (mostly UK Government bonds) back to commercial banks in order to slowly remove the money they’d created from the financial system, which should help reduce inflation. This was dubbed Quantitative Tightening. The Bank was unable to follow through though, because Kwasi Kwarteng’s mini-budget sent the government bond market into disarray.

The pursuit of unfunded tax cuts and generous fuel subsidies was in direct opposition to the BoE’s efforts to reduce the amount of borrowed money being spent in the economy and the huge and unexpected increase in government borrowing made the value of UK Government bonds plummet. Within days, pension funds (who typically own a lot of Government bonds) were on the brink of collapse and the BoE was forced to create more money and buy large quantities of government debt in order to stabilise the financial system. The absurdity of the government and central bank working against each other massively reduced investors’ confidence in the UK economy and the resulting drop in the value of the pound only made imported food and energy more expensive, thereby further stoking inflation.

The result has been that in the middle of an inflationary crisis, we had a central bank printing more money and a government increasing borrowing massively. This is the complete opposite of the orthodox response, like they’d been reading the textbooks upside down. When the BoE did eventually begin selling assets, it was in such low volumes as to have almost no impact.

Now we’re left with higher inflation that will last longer, and the very real possibility of recession still looms. This is incredibly frustrating for UK economists, since ultimately the UK’s economic woes are not extraordinary. They are textbook examples in need of a model answer and neither the central bank nor the treasury have been able to provide this.

But, like UK Government Bonds (which come on gold-edged paper), there is a shiny lining to the UK’s poor performance. Now that inflation is falling towards target in the US and EU (although not entirely banished), it is likely that UK interest rates will become comparatively high. This should bring a useful uplift to the value of the pound, making imports cheaper and helping to hurry inflation back to its target of 2% a year. Nonetheless, resolving inflation should remain a key priority for policy makers, before focus can shift towards broader economic objectives, such as managing the transition to net zero. Until inflation is brought back to target, Britain’s economic malaise is here to stay.