Upon sun bitten walls

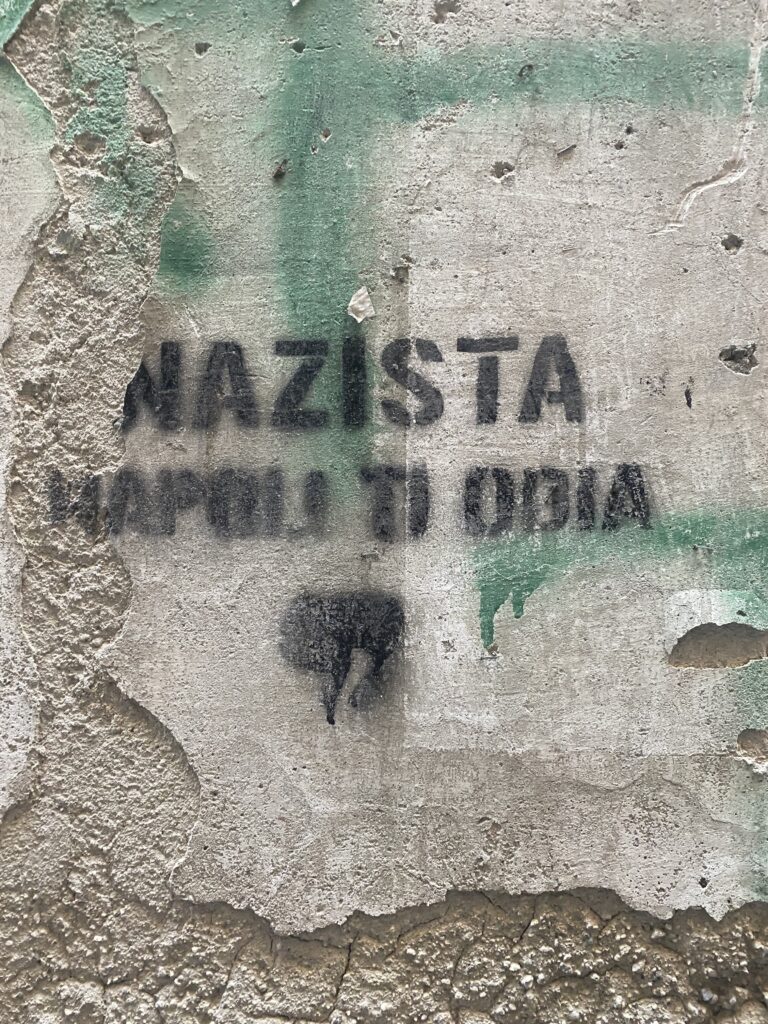

‘Nazista Napoli ti odia’; Nazi Naples, I hate you. These words stencilled in the city’s student quarter struck me during a trip to the domed city. Amongst mazes of apartment blocks, family shrines, SSC Napoli flags and advertisements for dangerously potent €2 spritzes were cries from a disaffected youth attempting to make themselves heard. Expressions of dissatisfaction through direct, functional means often following Marxist motifs colour the city’s sun bitten walls.

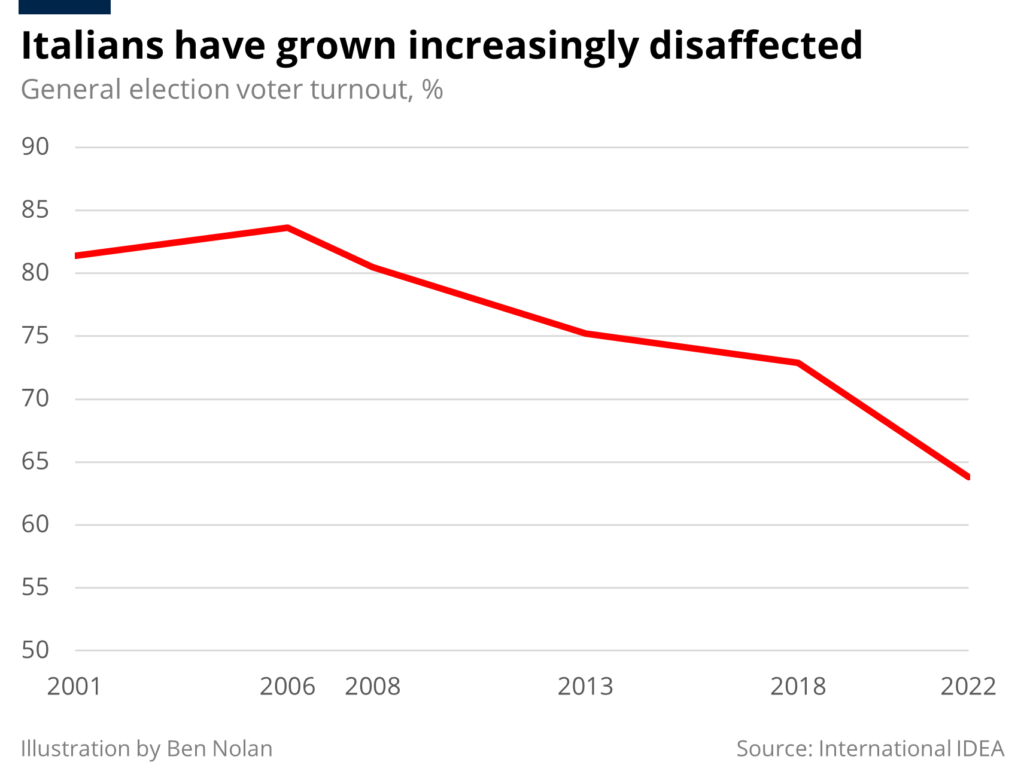

A visual conversation often mistaken for an eyesore. A visitor to Naples is subject to a war of words with graffiti as its very weapons. Every space is consumed from the Piazza del Plebiscito to a person’s own front door. In the wake of a gradually decreasing voter turnout which hit a low point of 63.9% in October 2022, a series of left-wing politicians have shown an interest in lending an ear to the unheard. Yet many ignore the very surroundings that scream to them. Often cloaked under far-left rhetoric the graffiti of Naples may provide the very information the left needs to win the next election. The writing is on the wall. Politicians need only read it.

Like a can of tuna

The 8th of September is remembered fondly amongst those within the Italian ‘5 Star Movement’ (M5S) party as, crudely, ‘Vaffanculo day’ (ask an Italian friend for a translation), the moment in 2007 that comedian and party co-founder Beppe Grillo addressed an audience of around one hundred thousand in Bologna on the corruption he believed was endemic in the Italian government. Two years later the party was formed as Grillo and tech entrepreneur Gianroberto Casaleggio attempted to put together a force they believed would break apart the technocratic structures and attitudes that had characterised their nation’s politics. They would finally provide an outlet for the unheard and disaffected.

From the outside the party appeared to be a left-wing force. Its 2018 manifesto had promised to expand the welfare state and combat climate change whilst reducing the number of MP’s and their salaries. In rhetoric the party attempted to present itself as a big tent, it was ‘neither left nor right wing’ but ‘a movement for Italians’. Its criticism of the political establishment did not express itself via the model of ‘class’ but instead ‘caste’ warfare. Through the rephrasing and reinterpretation of left-wing rhetoric, the party tried to open up the Italian parliament ‘like a can of tuna’, and in the process break apart a two-party system that had characterised Italian politics for over a decade.

Following years of campaigning, the party finally commanded enough momentum to achieve 32.68% of the vote share in the 2018 general election. The victory shocked both Italian politicians and commentators from both sides of the political spectrum. For a moment it was believed that the disaffected had finally triumphed. It was quickly realised that such a huge victory could not even pass through the Porta Triumphalis.

The killing blow

The problem with a big tent party is that you fail to keep track of everyone within it. As identified by the LSE researcher Antonio Belucchi, 8.4% of M5S voters had closer sympathies with the right-wing Lega party than it did with any alternative left-wing party. From its inception as the leading party, M5S was at risk of voters drifting to right-wing political blocs.

Covid provided what many saw as the killing blow to M5S’s place as the majority party. Disputes with other parties as to the direction the Italian government should take in dealing with the pandemic came to a head with the resignation of Prime Minister and M5S leader Guiseppe Conte. The party later agreed to support technocratic former European Central Bank Head Mario Draghi as Prime Minister, a clear betrayal of the very values that had delivered its success. In many ways it was this moment that secured M5S’s identity as another technocratic party rather than a political outsider. Despite previous success in changing the structure of government, the can of tuna remained firmly closed.

A champion of the disaffected

The sense of dissatisfaction with the Italian political system remains. M5S momentarily tapped into it. Many on the left have now realised that the ‘outsider party’ phenomenon is not isolated to one political grouping. In 2022 the far-right Brothers of Italy Party, that had otherwise been disregarded by commentators as political pondlife, leapt to the head of Italian politics. Whilst many viewed Georgia Meloni’s victory as shocking, the experience of 2018 has proved it to be far from surprising. As M5S suffered an identity crisis in government Meloni presented herself and her party as a different form of outsider, a new champion of the disaffected, to equal success.

Whilst Meloni celebrates an undisputed first year in government, she should try to deal with the elephant in the room. In 2022 turnout dropped by 9.09%, in 2018 the drop was a lower (but still concerning) 2.26%. The number of those who feel alienated or disaffected by the Italian political system has grown.The ‘outsider party’ phenomenon, whilst appealing to a small proportion of these voters, hides the fact that many still do not view voting as a worthwhile means of bettering their situation.

There is an increasing belief among Italian politicians that the next election will be fought over this group. To successfully appeal to them politicians will need to move out of the government buildings and into the streets. They will need to look and listen to those who feel unheard. So far, the leader of the Democratic Party has shown the greatest desire to try.

A little big revolution

On 12th March 2023 Elly Schlein surprised many within Italy when she became leader of the Democratic Party (PD). Schlein herself described her victory as a ‘little big revolution’. The victory was one of many firsts, the first female leader of the PD in a male dominated party, the first LGBTQ+ leader, the most left-wing leader in recent party history and the first leader to have left and recently re-joined the party.

A supporter of state mandated minimum wage, protecting public healthcare from privatisation and enshrining LGBTQ+ rights into law Schlein appears as the right-wing alternative to Meloni. In the few months spent leading the PD she has already managed to overtake M5S as the second most popular party.

Despite this early success, the overtake of Meloni as the leading party appears to be a much greater challenge. By setting herself the task of overtaking the Brothers of Italy Party Schlein has made herself a foreman at the head of a four-year project. The question remains as to whether she’ll be able to construct her supporter base from those who have previously felt abandoned by politics.

Abstentionism remains at the heart of Elly Schleins campaign. ‘Homo abstentious’ for Schlein is to be found amongst the ‘poorer segments’ of the Italian population. Schlein will need to relate to this type of voter on a personal level whilst offering them policies that will provide a tangible improvement to their lives. This is easier said than done. The daughter of wealthy parents, private school, and the University of Bologna, Schlein has some distance to cross. It is into this dilemma that the walls of Naples may provide clues in how to do it.

Mensa Occupata

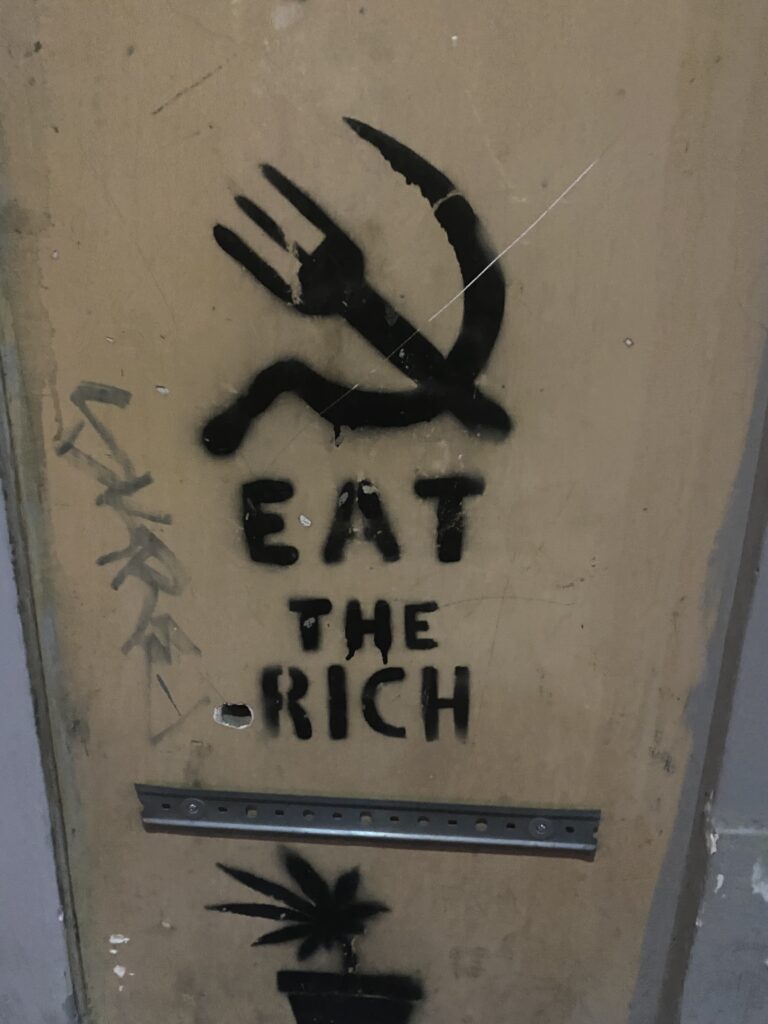

You’re never too far from graffiti in Naples. Research for this article involved walking around the streets attempting to discreetly snap pictures of interesting phrases or symbols written on the side of buildings. Sometimes this led to interesting conversations with locals, other times a muffed ‘vaffanculo’ (contacted that Italian friend yet?). There were a variety of political ideas displayed. Some were feminist and focused on destroying the patriarchy whilst uplifting the place of women in society. Others called for better wages. However, amongst an urban sea of ‘ACAB’, ‘Eat the rich’ and ‘Extinction Rebellion’ one mural particularly stood out to me.

It may have been the series of cheap spritzes (is ‘when in Naples’ a phrase you can use) I had drunk but the large black mural that contained a symbol of a hammer and sickle alongside the slogan ‘Class against class until victory’ appeared striking. From the offset this mural would be quite easy to dismiss. The slogan written on it has its roots in the most extreme period of early communism; the Third International, which announced an all-out class war to mark what they saw as the imminent collapse of capitalism. In a landscape where the end of days appears more likely than the end of the capitalist system such rhetoric feels lost. The mural itself, whilst fascinating, would have been kept as a curio on my camera roll if it were not for the name of an organisation in one corner.

‘Mensa occupata’, roughly in English ‘occupied canteen’ is a group that had originally established in November 2012 as a response to similar grievances to those that led to the formation of M5S, that being government ineptitude. The group initially sought to provide free and affordable food to those struggling in Naples yet in recent years their activity has greatly expanded.

Their Facebook group of 12K followers provides a list of activities, often linked with similar organisations such as SMASH Repression that aim to establish greater fairness within the judicial system as well as the protection of communal and social spaces. Under a thick exterior of far-left rhetoric and anti-establishment sentiment remains a wide body of potential policy ideas and popular sentiment that politicians could tap into.

Russo and Cospito

Two major issues have formed the focus of Mensa Occupata and allied group SMASH Repression’s campaign for greater judicial fairness. The removal of the law 41-bis that allows the placement of prisoners in complete isolation and the employment of armed plain clothes police officers.

The first issue came to a head in October 2022 when anarchist Alfredo Cospito who had been arrested for kneecapping an Italian energy company executive and suspected bombing was placed in isolation. Cospito protested the inhumane conditions he was placed in on the grounds that 41-bis had originally come into law to deal with mafia bosses and that its continued usage was an abuse of power. To further highlight his disagreement, he went on hunger strike with the support of outside groups such as Mensa Occupata. Many, especially on the far left, fear that the law could be further used as a tactic to suppress political dissent and as a result want it removed.

The campaign against plainclothes police officers was the result of the tragic death of 15-year-old Ugo Russo. The juvenile was shot dead whilst trying to rob a plainclothes policemen, a life sentence handed out in response to a poor lapse of judgement. The question as to whether plain clothes officers should be allowed or at least whether they should be armed has flared up because of this. Groups such as Mensa Occupata have protested in support of Ugo’s family. Opposition to the usage of this form of policing, surrounded by such recent tragedy does not necessarily appear extreme. If Meloni’s party looks to orient themselves around law-and-order, Schlein could counter through action and support for these cases to present her party as one of judicial fairness.

Occupied spaces

Public Spaces have also marked a key issue of defence for Mensa Occupata and similar groups. The occupation of public parks that are due to close down being one of the many ways the organisation has attempted to defend them. Alongside his Mensa Occupata has opposed laws which limit street artists and grant harsh sentences to those who organise raves in abandoned buildings.

Ultimately what Mensa Occupata aims to defend is a general communal sentiment. A world where there are spaces in which citizens can express themselves and meet others without fear of being observed by legal enforcement dressed to fit in amongst them. As someone who has orientated themselves as a champion of LGBTQ+ rights and expression, Schlein could easily tap into this sentiment and prove she can provide an ear to those who are firmly in the belief that the government is incapable of listening to them.

The writing on the wall

The purpose of this article is not to say that Italian politicians should start occupying parks. Neither is it to say that they should start to take on far-left rhetoric and ideas in their future campaigns. It is instead to suggest that politicians need to listen out for the details even when the calls from the electorate appear to be just shouting. In the case of Mensa Occupata, a mural that contained a very extreme far-left slogan was able to reveal an underlying sentiment that a centre-left party such as the PD could neatly embrace.

There is no point in claiming that you want to open the system if you are unwilling to listen to those for whom you are opening it for. There is no point in speaking for the people if you do not know who those people are. Political success in the next Italian election will follow those who are willing to really listen to the disaffected. This group does not need a champion, they just want an ear. If politicians fail to realise this, the writing is on the wall.