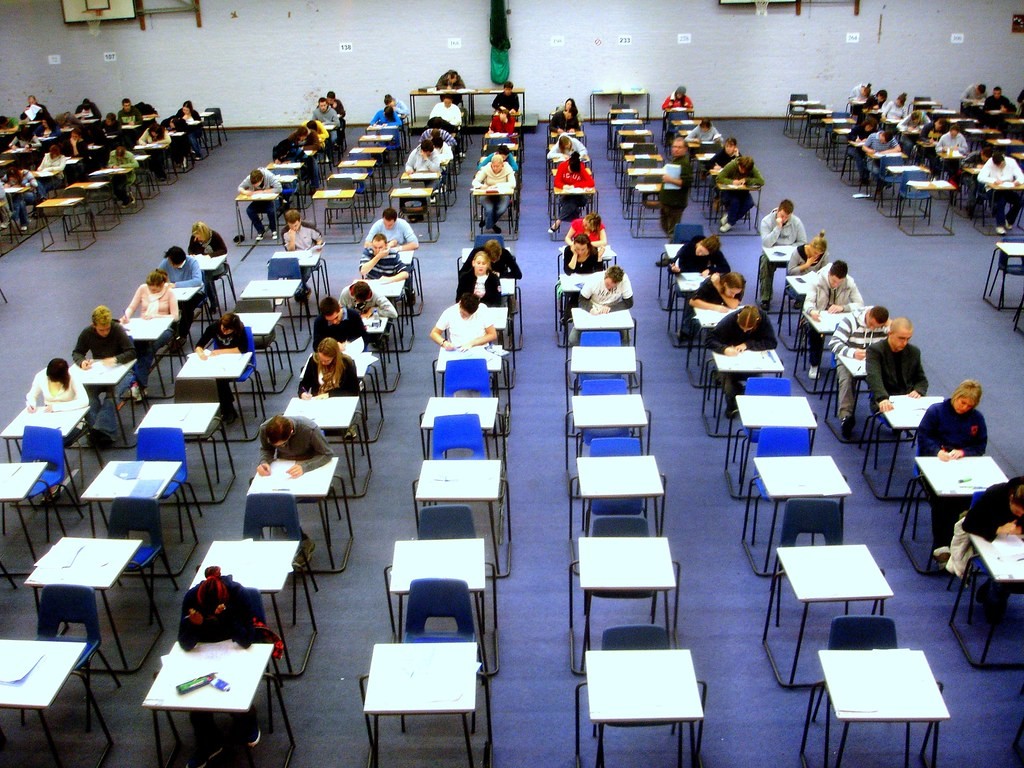

This August, hordes of students will pass through their school gates for the last time. You probably remember the feeling yourself – holding your future inside a brown envelope. Opening it with shaking hands, jumping for joy, or perhaps wishing you’d worked harder. Posing for pictures in the paper or sneaking past your teachers in shame. This year will be no different.

But what if we were to tell you that around ¼ grades awarded at GCSE and A level will be wrong? According to Dennis Sherwood, that’s exactly what will happen.

Dennis Sherwood

Having worked as a consulting partner in Deloitte’s and an executive director at Goldman Sachs, Sherwood now runs his own consulting business, Silver Bullet Machine. He became involved with Ofqual in 2013, when the regulator commissioned him to do a study on its system. Here, he noticed an interesting trend: though the number of candidates had decreased between 2009 and 2013, the number of challenges and appeals had increased. “You’d expect them to go together,” he tells us. “I then asked, ‘how many grades are wrong?’”

Ofqual’s response? 0.5% of grades are changed on appeal. “But that’s not my question,” Sherwood reiterates. Ofqual didn’t know how many grades were wrong – what if every grade that went unchallenged was wrong?

Changing Rules for Appeals

In 2015, Sherwood was working as an observer at Ofqual when he came across an announcement that they were changing the rules for appeals, which he believes made them harder to obtain. ‘That struck me as very strange,” he says, “Why would a regulator who is supposed to be protecting the interests of the consumer – the student – make it harder to appeal, to discover grading errors, and to correct them?”

It wasn’t until November 2016 that Ofqual published the first results of their inquiry: that one grade in four is incorrect. This was determined by having a set of scripts marked twice, once by ordinary examiners and once by senior examiners. Sherwood tells us that “in the Ofqual hierarchy, [senior examiners] are wiser than ordinary examiners”. In theory, the mark they give should be right.

For many, the conclusion they reached will be a cause for concern. Sherwood states that “if you take that entire cohort of many, many millions of scripts across 14 subjects, 25% of the ordinary examiner’s marks would have been overridden and changed by a senior examiner.”

This is no secret

In September 2020, Ian Mearns addressed interim Chief Regulator of Ofqual, Dame Glenys Stacey, at the Education Select Committee hearing. When asked whether she believed they should address the unreliability of 25% of grades, she replied that “we have faith in [the grades], but they are reliable to one grade either way”.

But should we have faith in these grades?

“I think there are two questions,” Sherwood tells us. Firstly, “does it matter?”, and secondly “do you care?” Here, I ask you a simple question to determine this: would you accept a downgrade in your results, knowing that you deserve something better?

The Perfect Crime

For this reason, Sherwood argues this is “the perfect crime”: the crime is obvious, and yet the victims are unsuspecting. You are given your grades in good faith, and you believe they are the grades you deserve. But, as he points out, “you live in the city of Morse and Lewis. If you [asked] them ‘what would a perfect crime look like?’ They would say the victim doesn’t complain, and the perpetrator gets away scot free”.

Although Sherwood tells us that “it’s been in the press since [2016]”, the pressure on Ofqual has not been sustained. A low percentage of students know they are victims of grade variability because they accept the grades they are given, and so media attention on the issue is negligible. Education can transform your life, and yet this discovery suggests that people may be being held back by the system itself.

What is the solution?

In the short term, awareness, which is exactly what Sherwood aims to create with his book Missing the Mark, which will be published this August. “Schools, teachers, parents, and teachers [need] to lobby Ofqual and their MP and say ‘this is unfair’”. For students, this also means knowing your grade could be wrong and submitting an appeal. After all, “it could be that every grade that has been unchallenged [is] wrong.”

Of course, this shouldn’t be the way. “In the longer term, and what, of course, should have been done during the two-year break [from exams during the Covid-19 pandemic] is to change the way grades are.”

“In the future […] some computer in the sky will mark the script.” But in the meantime, Sherwood suggests that we should “throw grades away and have certifications” which state the candidate’s marks, plus or minus five. “We have to stop using this as a means of discriminating between people.”

Ultimately, Sherwood believes that “grades done wisely makes sense.”

You can find Sherwood’s book here: