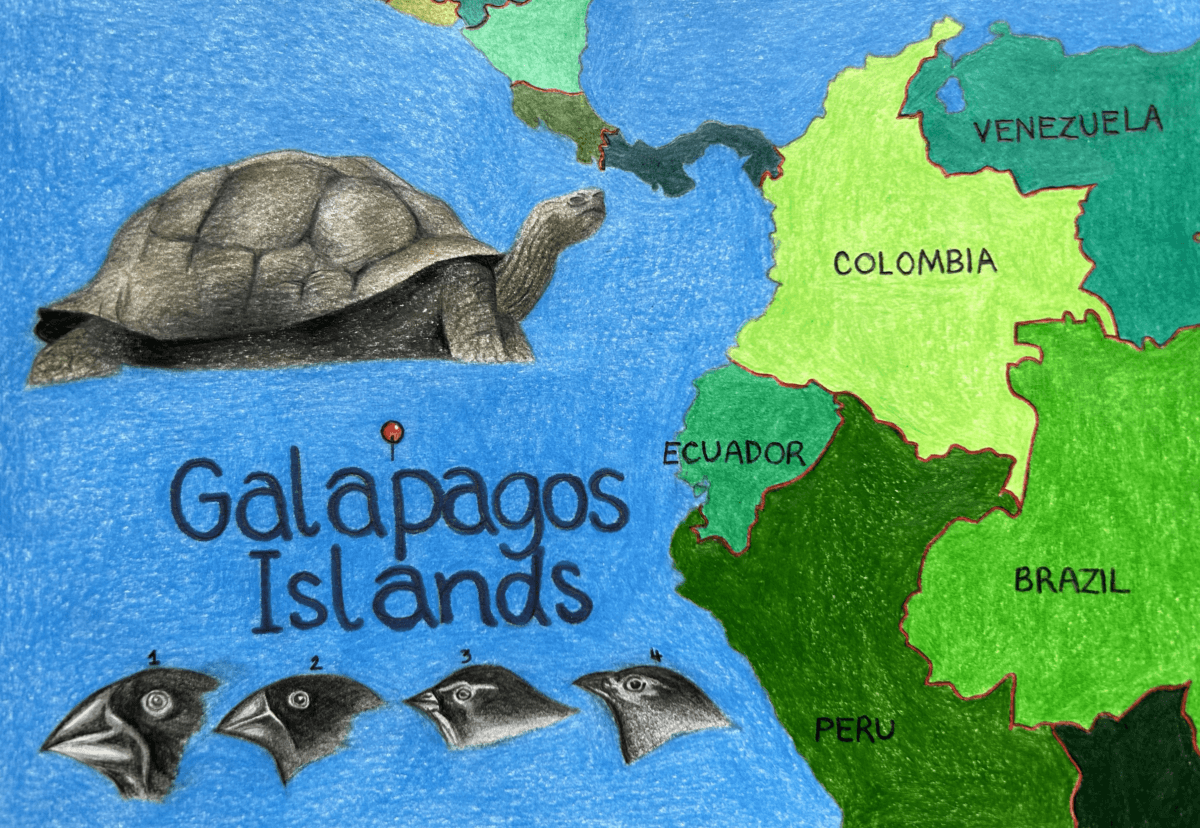

Located in the Pacific Ocean, around 1000km west of Ecuador, lie the Galapagos Islands. The islands are volcanic in nature, produced by a plume of molten material rising up from the Earth’s mantle to melt the crust above it. This plume is known as a hotspot and its activity has produced a chain of 13 major and numerous smaller islands over the course of millions of years. Most of the islands are conical, consisting of a single, steep-sided volcano which stretches skywards, breaching the surface of the ocean. Over time, the number of islands in the chain will alter. Old islands will subside below sea level and new islands will form.

The Galapagos Islands are perhaps best known for harbouring a wide variety of plant and animal life. The WWF reports that together the islands boast 9,000 different species. This is particularly significant as a large proportion of these species are endemic, meaning they do not exist anywhere else on the planet. The Galapagos Conservancy estimates that 97% of land mammals and reptiles, 80% of land birds, 30% of marine species and over 30% of plants found on and around the islands are endemic. Renowned endemic species include the Galapagos giant tortoise, Galapagos penguin, and marine iguana.

The island chain has a wide range of species, with a high proportion of endemism, for two key reasons. Firstly, the steep sloped islands provide numerous different habitats both on and offshore, including sand dunes, highland forests, and coral reefs. This variation creates ideal conditions for many different species. Secondly, the island chain is isolated, with the nearest continent (South America) lying approximately 1000km away. Isolated islands are associated with high levels of endemism as species cannot colonise them on foot; therefore, they are forced to fly, swim, or raft across the ocean. Upon arrival, successful colonisers often undergo evolution to fill empty niche space in the ecosystem, thus producing new, endemic species.

In perhaps the most famous research completed on the island chain, naturalist Charles Darwin studied this process while developing his theory of evolution. He observed that a single bird species had evolved into multiple different species (later coined Darwin’s finches), each of which possessed a unique beak size and shape, allowing them all to thrive on different diets. By acting as natural laboratories, the biodiversity-rich Galapagos Islands still provide excellent research opportunities today.

Unfortunately, the biodiversity of the island chain has seen a decline. An increasing number of species have become threatened and some, such as the Pinta Island tortoise, have already become extinct. This is largely a result of damaging human activity, which still persists in spite of the National Park status attributed to 97% of the islands’ surface in 1959. The islands are home to around 30,000 people and they receive around 200,000 tourists per year. This has promoted destructive activities such as deforestation, pollution, overfishing, and the introduction of invasive species. Together, these activities damage habitats and make the survival of existing species extremely challenging. Species receive further pressure from anthropogenic climate change. The equatorial position of the chain makes it particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events and rising temperatures, with land temperatures increasing by an average of 0.6°C since the 1980s.

In a crucial attempt to prevent further extinctions and protect existing Galapagos ecosystems, numerous conservation projects have been initiated. The Galapagos Conservation Trust (GCT) is a British charity founded in 1995 with the purpose of spearheading such projects. Current GCT projects are attempting to rewild the Galapagos Islands. Their aim is to reduce damaging human influences and allow natural ecological processes to resume.

The GCT list three predominant strategies for rewilding the island chain. Firstly, controlling the estimated 1,500 invasive species present on the island chain that have the potential to disrupt existing ecological communities. For instance, rats and feral cats, transported to the islands by humans, have been known to feed on birds, iguanas and giant tortoises, placing greater pressure on the survival of these species. Attempts to reduce invasive rats have already had promising results: Pinzon Island was cleared of invasive rats in 2012 and is now showing signs of ecological recovery. Secondly, the GCT aim to restore habitats on the islands by reinstating vegetation present there before human intervention. Finally, the GCT are working to reintroduce keystone species, such as land iguanas and giant tortoises, which have a disproportionately significant impact on the upkeep of their ecosystem.

To raise awareness for their important conservation work throughout the Galapagos Islands, each year the GCT holds ‘Galapagos Day’. Galapagos Day 2023 is taking place on the 19th of October, with the theme being ‘Rewilding Galapagos’. At the Royal Geographical Society in London, an evening event is being held to mark the occasion with speakers, stalls and photography displays. Tickets to the event are just £15 per person and £10 for students, with all proceeds being put towards the conservation work. This is a great opportunity to find out more about their valuable conservation efforts and to personally contribute towards the protection of the Galapagos Islands; one of the most unique and vulnerable areas on our planet.

Comments are closed.