After three years of draconian “zero-COVID” policies, citywide lockdowns and shut borders, China finally began to lift its restrictions at the beginning of this year. The stringent lockdowns had essentially shut down the world’s second largest economy by GDP (and the largest by purchasing power parity, accounting for the cost of living), with economic growth falling to its lowest levels since China opened up to the world’s economy when it joined the World Trade Organisation in 2001. Economists would have thought that eight months after re-opening, China’s economy would be roaring back to life; yet so far we have only heard a faint whimper. The reasons behind it run deep, yet the prospect of recovery remains greatly uncertain.

Sino Slowdown

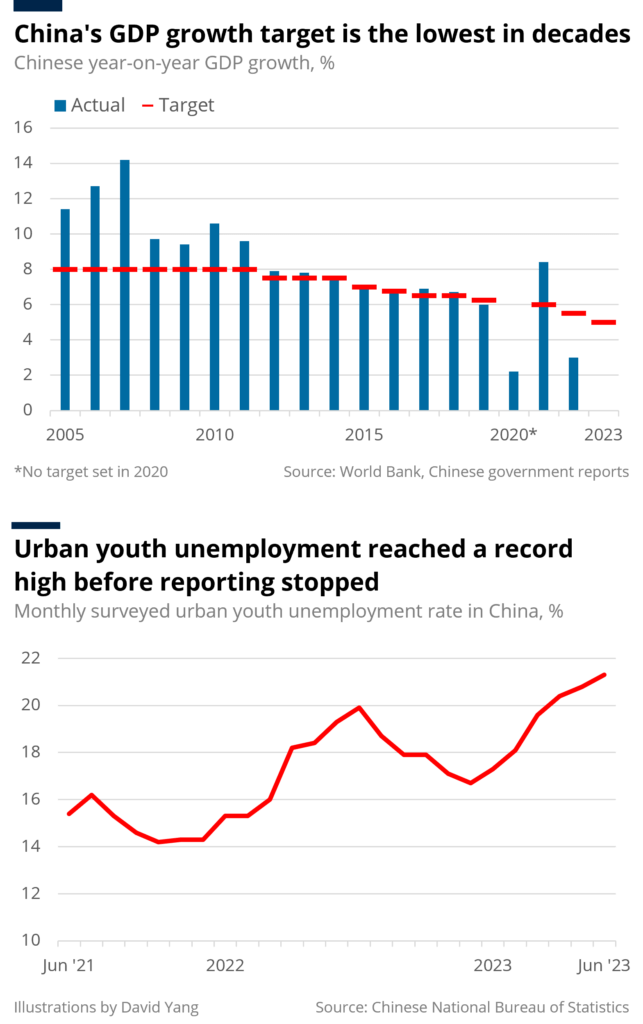

The first major sign of lacklustre economic performance came from the Chinese government itself. Every year, the government puts out growth targets for the economy, and in March the 2023 target was announced to be “around 5%”. The goal was noted for being the lowest in decades, at a time when the economy should be making a rapid recovery from years in lockdown. Yet as time passes the already pessimistic goal looks increasingly difficult to achieve.

A slew of disappointing statistics released over the course of the year have laid bare the economic malaise within China. Factory activity shrunk for the fifth straight month in August, and retail sales growth has slowed to near stagnation. Trade volumes declined, with exports and imports down 8.8% and 7.3% on a year earlier, respectively. While most developed countries struggle with high inflation, China has begun to dip into deflation, which only worsens the fall in demand. As prices fall, consumers are incentivised to defer spending, which causes prices and demand to fall further in a deflationary spiral. At the same time, the Chinese Yuan has fallen to its lowest level since 2007.

In a humiliating admission of their failures, the Chinese government has hidden some of their more embarrassing statistics. The National Bureau of Statistics abruptly suspended their reporting of consumer confidence and urban youth unemployment, which have reached record lows and highs, respectively. Yet hiding them has only served to deepen observers’ worries about the state of the Chinese economy. These worries have only grown after China’s central bank disappointed with a smaller-than-expected interest rate cut of just 0.1% in August, doing little to stimulate China’s faltering economy.

It is clear that China suffers from a crisis of confidence: consumer demand and business investment are wallowing at record lows. Yet poor confidence is merely a symptom of the much deeper problems within the country. Three failings underpin China’s flagging economy: property, policy, and politics.

Property Pitfalls

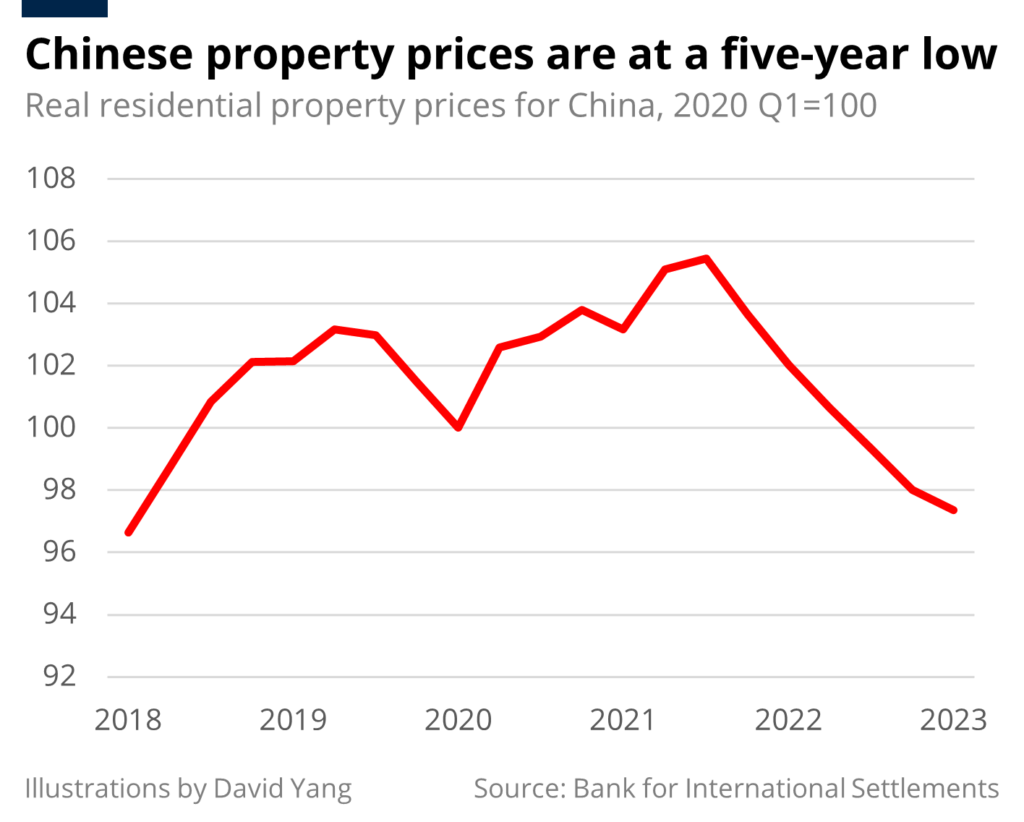

China’s real estate sector has teetered for several years now, ever since property giant Evergrande defaulted on its debt payments in 2021. China’s housing market had boomed in the decades leading up to then as a growing population, cheap credit, and government support for house building led to aggressive expansions by developers, who borrowed heavily to fund new projects with the assumption that demand for housing would continue to grow. Yet as China’s population ages, with population falling in 2022 for the first time since the 1960s, housing supply has outpaced demand, causing real estate prices to plunge to their lowest level in five years.

As house prices fall, developers’ revenues have fallen to the point of being unable to pay interest on their loans. In August, Evergrande declared bankruptcy on its more than $USD 300 billion of debt. Shortly after Country Garden, which the Chinese government had informally classified as a “healthy” developer, reported losses of $6.7 billion for the first half of 2023. Even amid optimistic news of recovering industrial production and retail sales in September, observers remain gloomy over the prospect of property investment plummeting by 19.1%. The sheer size of these property developers, considered to be “too big to fail”, poses an acute risk to China’s financial system. Banks that have loaned to developers face huge losses and risk collapse themselves, which would spark a full-on financial crisis.

Paradoxical Policy

Yet policy offers little hope of relief. Immediate solutions would have included local government support for banks and developers, were they not strapped for cash themselves. China’s local governments are barred by the central government from directly raising debt themselves, and resort to leasing land to developers as a primary source of revenue. Given the current crisis stems from the property sector, additional funding from land sales looks increasingly unlikely. This combined with already drained finances from the strict years-long lockdown, particularly among China’s lower tier cities, leaves the hope of any support with the central government. In the last decade the Chinese government would have been more than willing to provide generous economic stimulus as they did in 2008, managing to avoid a recession entirely. Today, however, this level of aid will not be forthcoming. President Xi Jinping has turned the page on the Chinese government’s economic policy consensus, launching his “Common Prosperity” campaign in 2021. A shift in rhetoric and attitudes against big business in favour of those “left behind” has meant the government is reluctant to bail out large corporations, leaving investors, businesses and consumers uncertain.

Beyond just the property sector, President Xi’s policies have proven to be unhelpful to the wider economy. Within the Common Prosperity campaign was a crackdown of private technology and tutoring firms, the most notable example being Alibaba founder Jack Ma’s fall from the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) grace. It is the restrictions on the private sector in particular that make the youth unemployment crisis so severe, as tech and tutoring jobs were among the biggest employers of new graduates. Yet if one expected the harsher rhetoric towards businesses to be accompanied by greater generosity for ordinary citizens, handouts to the poor are unlikely as well. A desire for greater fiscal restraint has led Xi to decry “welfarism” and vow to “not raise appetites” for increasing funding for public services or transfers. Indeed, the CCP’s response to souring economic conditions for young workers is to pull themselves up by the bootstraps and “toughen up”.

Problematic Politics

Not only being the root of China’s policy failures, Xi’s politics are also worsening China’s economic prospects. The technocrats that spearheaded China’s rapid economic growth in the 2000s and early 2010s have been replaced with loyalists to President Xi. As power and influence centralise around Xi Jinping, his ideology will become further entrenched into policy making.

Since coming to power, Xi has intensified nationalist rhetoric and drummed up patriotism, prioritising the “reunification” of China. What started with repression in Hong Kong and Macao will culminate, he hopes, with the end of an independent Taiwan. With this comes Xi’s more global, assertive, and expensive vision of Chinese foreign policy. The Belt and Road Initiative, China’s massive campaign of infrastructure investment to developing countries to spread its global trade network, has proven to be a financial drain as dozens of developing countries have defaulted on Chinese loans, forcing China to provide $USD 240 billion worth of bailouts. To strengthen its hold in the Pacific and prepare for a likely invasion of Taiwan, China has ramped up military spending and is expanding its nuclear arsenal. The focus of the CCP is no longer economic growth, but national security.

This new hawkishness carries more than an economic cost. Although the US’ “pivot to Asia” started during the Obama administration, successive presidents have only become more assertive towards China. From former President Donald Trump’s trade war to President Joe Biden’s sanctions on microchip exports to China, the US has taken an increasingly hostile stance towards China’s geopolitical ambitions, joined not only by Europe but by many in China’s neighbourhood. Biden has rallied traditional Asia-Pacific allies such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and the Philippines to unite against China, while also reaching out to regional powers such as India that are sceptical of China’s growing influence. So long as China continues with Xi’s assertive foreign policy goals, it appears that other nations will keep China at an arm’s length.

Domestic Problems, Global Consequences

The sheer size of China’s economy, both as a giant consumer market and production hub, has always meant that fluctuations in the Chinese economy have a significant impact on the rest of the world. The downturn today is already having pronounced effects across the world. China’s cooling demand for global goods has hurt exporters in Asia, Europe, and the US. In Europe particularly, where Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the accompanying soaring energy costs have taken a toll on the region, falling Chinese demand has crippled German car manufacturers and threatens to tip the country into a recession. For the US, where growth is still strong, China’s slowdown does provide some respite from interest rate increases – as Chinese demand for US goods falls, the tight labour market will likely ease, thereby reducing inflationary pressure. However, should the Chinese economy fall into a deeper recession, the economic pain will be felt everywhere as the world’s largest consumer market of international goods grinds to a halt.

If China’s economy continues to do worse, it will not only harm Chinese citizens, but have profound consequences for economies across the world. At a time of high interest rates, high inflation, rising oil prices, and global insecurity, recession in the world’s second largest economy is the last thing that is needed. The global economy is not a zero sum game, but is reliant on stable and secure global cooperation.

It is evident that President Xi Jinping’s dogmatic politics is doing the Chinese economy no favours. Yet as control over China’s institutions is increasingly held by political loyalists, any challenge to his ideological dominance seems improbable. The direction of Chinese government policy is very much dictated from the top downwards. So long as that remains unchanged, the direction of China’s economy will likely follow suit.