When was the last time you viewed the content on someone else’s social media feed? Last week, I was sitting behind a man on the bus. I was on one of those raised seats, providing the perfect vantage point for a good snoop at his digital activity (I won’t make a habit of this). For the entirety of the 20 minute journey, I watched him scrolling his Instagram feed — a depiction of an entirely different world to the one I thought I was living in. Where my carefully curated timeline had convinced me that every sensible person was worried about the rise of Reform UK, environmental protection, and the large-scale loss of innocent life, his feed was quite different. Our respective algorithms had just been showing us what we wanted to see; reinforcing our existing individual ideas about the nature of reality. That’s a problem.

It’s profoundly unsettling that the technology we use to continually inform ourselves about the world’s happenings is actually hindering our ability to understand the world. This problem isn’t the sole responsibility of social media. It runs far deeper. We are in the grip of an epidemic of black and white thinking — a compulsive need to sort everything into defined camps. Good or bad. Friend or foe. Left or right. Worse still, this is in fact a deeply ingrained feature of human psychology.

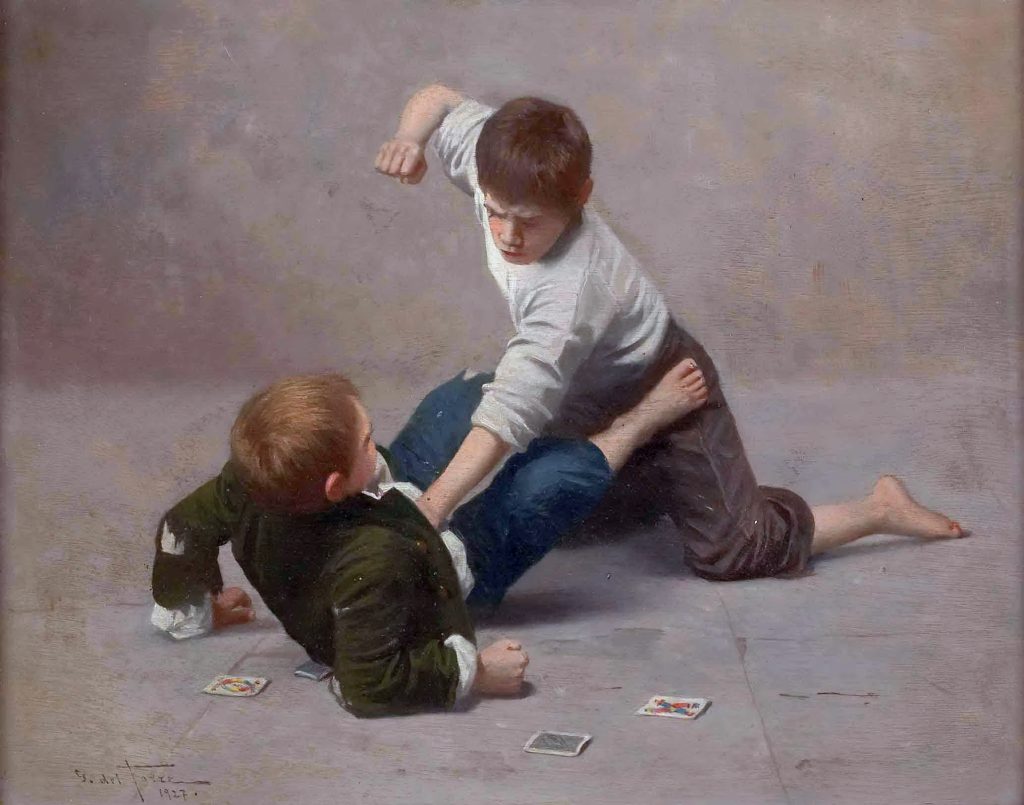

The snap judgments that we make aren’t made by accident; they’re echoes of a brain that evolved in a time where the ability to make these rapid categorisations was a matter of life or death. To quickly distinguish between tribal allies and potential threats was essential. It was those who did this effectively that were able to keep themselves safe, and live long enough to pass on their genes.

This cognitive machinery served us well when we lived in groups of up to 150, and the presence of genuine physical threats were frequent and acute. In 2026, that same cognitive machinery is less helpful. The same instincts that once kept us alive now keep us intellectually impoverished, leading us to quickly categorise individuals — often politically — based on fragmentary evidence. People are far more complex than we often give them credit for.

For a human brain, the appeal is clear. Thinking is genuinely hard work. Genuine reasoning — holding multiple contradictory ideas simultaneously, updating beliefs when presented with new evidence — is inconvenient and incredibly taxing. It is far easier to post-rationalise our behaviour and warp incoming information to fit our existing beliefs about the world. It preserves what is referred to within psychology as ‘cognitive load’, while providing the comforting illusion of understanding.

This deep-rooted human tendency has been weaponised by social media very cleverly. The algorithms are calibrated in such a way that they drip feed us fuel for confirmation bias, delivered so effectively that we begin to mistake our echo chamber of a feed for reality.

What we lose is the acceptance and appreciation of nuance. We lose the ability to see issues as incredibly complex, and appreciate that there are often credible arguments on both sides of a debate. With this, we see a decline in intellectual humility, people’s openness to having their mind changed, and the ability to see the world as far more complicated than we could ever comprehend. The cost of this shift is evident in political discourse that reads like propaganda: in the casual confidence with which people dismiss vast portions of fellow human beings as irredeemably evil or stupid.

Say what you like about the institution, but the University of Oxford can’t be faulted when it comes to attempting to remedy this proclivity for binary thought. There is a relentless focus — particularly within tutorials and seminars — on the consideration of the value of sources, awareness of alternative viewpoints, the extent to which theories transcend time and space, and the frequent need to take a step back and see the bigger picture.

Unfortunately, this is only a partial antidote. You cannot will yourself out of millions of years of evolutionary pressure, and social media platforms’ economic incentives align perfectly with the intellectual instinct to make impulsive judgements. But recognising the problem may be the beginning of addressing it. The next time you find yourself categorising someone based on limited information — their political views, their background, their associations — it might be worth pausing to ask yourself: what else might be true about this person that contradicts the story I’ve just constructed?

The alternative is to continue to inhabit a world where individuals are quickly cast into preconceived roles — fuelling resentment, hostility, and division.