Lola Dunton-Milenkovic

On 3 January 2026, the United States conducted a military operation named “Absolute Resolve” across Venezuela to capture President Nicolás Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores. Planning for the intervention reportedly began in August 2025, with an intention to be carried out four days before 3 January, but was delayed due to weather conditions. Late at night, 150 US military aircraft soared into Venezuela. Forces arrived at Maduro’s compound in Caracas just after 2am, where he and Flores surrendered. There was no loss of life from the American side, whereas Venezuela’s interior minister claims 100 people died in the attack, which may include Cuban military and intelligence personnel who assist Venezuela.

This invasion represents the culmination of a tension that has been rising since August 2025, when the US began deploying Navy missile destroyers and military personnel at the edge of Venezuelan territorial water, supposedly to thwart drug trafficking. Since September, at least 115 people have been killed in more than 30 US strikes on boats in the Caribbean and Pacific, accused of transporting drugs, though no evidence has been provided to support such claims. In December, tension increased when the US military seized an oil tanker off the coast of Venezuela, claiming the tanker was transporting Venezuelan oil sanctioned by the US. Venezuela accused the Trump Administration of “piracy”, and a week later Trump announced an oil blockade on Venezuela.

The US has framed the operation as part of a campaign against illegal drugs. This stems from 2020 when the Justice Department during the first Trump Administration charged Maduro with allegedly running a narcoterrorism conspiracy.

However, Trump has suggested other reasons for the invasion too: that the operation was a means of forcing a regime change, that it formed part of his new approach to foreign policy called the “Donroe Doctrine” (a revival of the Monroe Doctrine from 1823 to oppose interference in the Western Hemisphere), and that Venezuela under Maduro was “hosting foreign adversaries” and “acquiring menacing offensive weapons” that threatened US security. Trump has also expressed a desire to control Venezuela’s oil industry, claiming the country had “stolen” it from the US. Herein lies the heart of the matter: oil.

So what is so special about Venezuela and its oil? What led to the events of 3 January 2026? And what does this all mean for the future of Venezuela and global politics?

A Modern History of Venezuela

The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela is a country located in the north of South America. With a population of 28 million people, it is bordered by Colombia, Brazil, Guyana, and the Caribbean Sea. It is, above all, a famous petrostate, and is home to the world’s largest oil reserves. Since the 1930s, Venezuela has served as one of the main producers of oil in the world. In the first half of the 20th century, though, the industry was in the hands of foreign companies, and the Venezuelan government was occupied with political crises. These include a dictatorship in 1937, a military junta in 1945, a military coup in 1948, and a military dictatorship from 1951 to 1957.

However, things changed in 1958. Marcos Pérez Jiménez’s military regime collapsed, overthrown by popular opposition, leading Venezuela to experience three of the best decades in its history. This is when it had the fourth-highest GDP per capita globally and bore several nicknames including ‘The Millionaire of America’ and ‘Saudi Venezuela’ due to its oil wealth. The country prospered; between 1959 and 1983, unemployment was steady at around 10%. Unlike in neighbouring Latin American countries, prices did not rise with inflation, and the bolívar (the local currency) was stable.

During this time, Venezuela was a booming country with the tallest modern buildings in Latin America, bustling highways which traversed between mountains to connect Caracas with the Caribbean coast, and luxurious hotels. It even earned the position of the highest consumer of whisky in the world.

Democratic governments inherited this same infrastructure, ensuring unprecedented political and economic stability, with good relations between civil and military power. It was the closest Venezuela ever came to resolving its greatest problem: dependency on international oil prices. This progress was aided by the construction of the Guri Dam, or the Simón Bolívar Hydroelectric Plant, in 1963, and the steel corporation Siderúrgica del Orinoco (SIDOR) in 1964.

The early 1970s continued to bring an economic boom to Venezuela. The country established majority ownership of foreign banks, took control of the natural gas industry, and declared a moratorium on the granting of oil concessions. The Yom Kippur War in the Middle East in 1973 caused oil prices to skyrocket, and as a founding member of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Venezuela more than tripled the price of its oil. Here enters President Carlos Andrés Pérez, who in 1975 nationalised the iron ore industry, and the following year nationalised the petroleum industry. Pérez represented the pinnacle of three successful governments. He achieved many things: he created a friendly relationship with the US, conserved resources, passed measures to stimulate small businesses and agriculture, created the Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho Foundation (attempting to create the so-called “brains of a future Japan”), and channeled petroleum income into hydroelectric projects, education programs and steel mills. Under him, Venezuela was booming. The second largest cultural centre in the region was built in 1973 (the Teresa Carreño Theatre), and various cultural staples from arts centres to museums were opened.

However, the economic prosperity did not last. An international recession and oil glut in the late-1970s slashed world oil prices, plunging Venezuela into economic stagnation. Continuing into the 1980s, this saw a downward trend in gross domestic product and an increase in inflation. Exports declined, unemployment grew, and capital flight took root with investors shifting their capital to foreign markets. The economy had entered a crisis. It became evident that the windfall resulting from the economic growth of the 1970s had brought luxury only to a privileged economic elite, and in reality had actually done very little to alleviate poverty. The subsequent governments found themselves unable to repay foreign debt: Christian Democrat Luis Herrera Campins was forced to devalue the currency for the first time in two decades, and Democratic Action’s Jaime Lusinchi adopted limited austerity measures to slow capital flight. By 1988, another drastic decline in world oil prices cut government income in half, and repaying the aforementioned foreign debt became increasingly difficult.

Pérez returned to power in 1989, and while he sought to deal with foreign debt on a region-wide level by stimulating growth domestically, his popularity became short-lived. Riots broke out across the country in response to a rise in bus fares, which formed part of a series of austerity measures announced in 1989. Looting ensued, and troops killed hundreds of people in an attempt to quell disturbances. The early-1990s were characterised by protests, labour strikes, and heated political debate as Pérez attempted to reduce tariffs and decrease government intervention in the economy. In 1993, he was forced to leave office for misappropriating funds.

By 1998, more than half the Venezuelan populace lived below the poverty line, annual inflation exceeded 30%, and oil prices were in steep decline. What remained in the minds of the people, however, was a time of luxury: petrodollars, political stability, and opulence. These memories only served to foster discontent, culminating in 1999 when the majority of Venezuelans – who by now were fed up with traditional parties – elected a soldier who was promising change: Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez.

Chávez’s actions were at times positive. He managed to spend petroleum income to fund social programs. He also created a strong relationship with Cuban President Fidel Castro, supplying petroleum to Cuba and other developing nations at cut-rate prices, determined to reduce US economic influence in South America and promote Mercosur (a South American regional economic organisation). In 2007, Chávez renationalised the petroleum sector. Venezuela then assumed operational control of the oil industry in the Orinoco basin (the world’s single largest known oil deposit) from foreign-owned companies. However, Venezuela entered the pattern it has always succumbed to: the country grew while there was an oil boom, but the good times only lasted until the prices of petroleum fell.

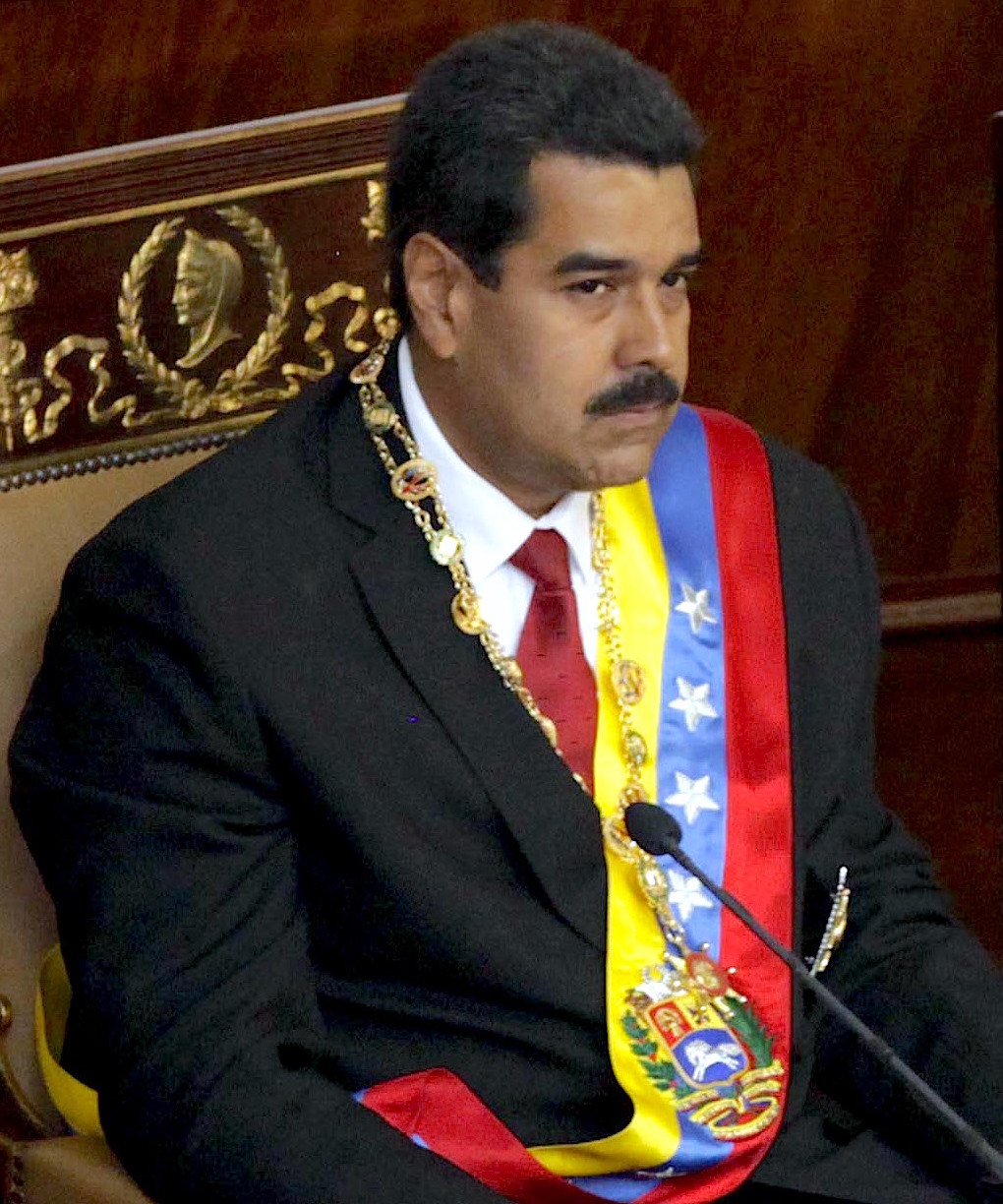

When Chávez died of cancer in 2013, his Vice President and mentee at the time was elevated to the presidency – and here enters Nicolás Maduro. That year saw the country’s economy slow drastically, with inflation climbing above 50%. Discontent with the Maduro government’s handling of the economy and the growing crime rate led to street protests by students in 2014, and a violent retaliation from security forces that resulted in a dozen deaths.

With declining world prices, the economy continued to struggle. In 2015, GDP tumbled and inflation ballooned. By 2018, the economy was in shambles. Maduro went from authoritarian to dictatorial rule, resulting in sanctions from Europe that joined those already imposed by the US. Venezuelan oil production plummeted, the country’s GDP suffered another crippling decline, and shortages of food and medicine were endemic. Hyperinflation orbited at 2,400%, and the bolívar became worthless.

Maduro continued to declare victory in subsequent disputed elections in 2018 and 2024. Several countries however, including the US, have not recognised his victories and consider him an illegitimate president.

From Riches to Rags

“We were rich and we did not know it” is a saying that plagues Venezuelans today, who once used to say “it is cheap so give me two”.

Poverty has become the norm in Venezuela. It is now one of the poorest major economies in Latin America. Since 2017, the share of households living under the poverty line has surpassed 90%. As of 2026, 7.9 million people in the country require humanitarian assistance. Out of a population of 28.8 million, over 20 million Venezuelans live in multidimensional poverty due to economic precarity and poor public services. Hunger faces 5.1 million people because of economic sanctions and the political instrumentalisation of state food programs.

There is a raging refugee crisis. Since 2014, roughly 8 million Venezuelans have left the country, of whom about 6.5 million relocated within Latin America and the Caribbean. Due to movement restrictions like visa requirements or poor integration programs, many venture into the Darién Gap. This is a dangerous jungle on the Colombia-Panama border, where refugees are exposed to abuse including sexual violence, and where hundreds go missing. In 2023, over 500,000 people crossed the Gap, heading to the US.

Freedom of expression continues to be limited. Espacio Público, a free-speech group, registered 507 violations to the right of freedom of expression between January and August 2024. These included intimidation, censorship, and judicial harassment. In the same period, 19 press workers were detained, 15 radio stations were closed by the national telecommunications authority, and at least 35 digital news and NGO websites were blocked by government authorities, such as political content platforms, X, Wikipedia, and the encrypted messaging app Signal.

Indigenous peoples are particularly disproportionally impacted by “malnutrition, extreme poverty, as well as exposure to diseases and environmental degradation in part due to extractive activities within their territories”. Above all, illegal mining activities and violence have displaced many Indigenous communities.

A Look into the Future of Geopolitics

The biggest outcry following Trump’s invasion was around whether he was entitled to commit such an act. Trump never formally declared war on Venezuela, despite such an aggressive military campaign and the ousting of a leader. In an interview with NBC on 5 January, he specifically reiterated that the US is not at war with Venezuela, rather it is “at war with people that sell drugs. We’re at war with people that empty their prisons into our country and empty their drug addicts and empty their mental institutions into our country”. The Trump Administration has therefore justified the attack using the President’s Article II constitutional powers. These grant him the authority to defend the country against threats – which in this case are the Venezuelan drug cartels that the administration defines as terrorist organisations.

However, legal experts and lawmakers have questioned the legal basis for Trump’s attacks on Venezuela. They argue that the US has indiscriminately killed civilians without due process, and has used sustained force against Venezuela without clear evidence of an imminent threat or explicit congressional authorisation. Several members of Congress, too, have described the Administration’s actions as “wildly illegal”. France, Spain, Brazil, China, the European Commission, and interestingly Russia have all declared that Trump broke international rules.

A spokesperson for the UN said that the US’s actions made “all States less safe around the world” and added that “Far from being a victory for human rights, this military intervention, which is in contravention of Venezuelan sovereignty and the UN Charter, damages the architecture of international security”.

Some have raised concerns that this may be the first of many attempted US interventions under Trump, who has hinted at targeting other countries. This includes Colombia, whose leader Gustavo Petro has been accused by Trump of failing to curb its supply of cocaine to the US.

The intervention may also signal to US adversaries like Russia and China that they can attempt similar takeovers, such as with Taiwan for the latter.

A Brief Look at Venezuela Today

Maduro is accused of narco-terrorism, conspiracy to import cocaine, and several other charges. Flores, his son, and other Venezuelan officials have also been charged. On 5 January, Maduro and Flores pleaded not guilty in court appearances in New York. They were then remanded in US custody. While Maduro and Flores remain in the Metropolitan Detention Centre in Brooklyn, waiting for their next court appearances on 17 March, Venezuela is changing.

Following Maduro’s capture, his Vice President Delcy Rodríguez was sworn in as Venezuela’s interim president. Former minister of Petroleum, Rodríguez received the public backing of the Trump Administration, although Trump has threatened that she would “pay a very big price, probably bigger than Maduro” if she does not submit to US demands. The Trump Administration has also said that Venezuela will not hold elections in the next 30 days. Instead the US will “run the country” until a time where the country can have a “safe, proper, and judicious transition”. Rubio has clarified that the US government intends to influence Venezuela’s political future and assert control over its oil industry by placing pressure on the country’s government, rather than directly governing it. Trump added that US oversight of Venezuela could last for years.

A longtime Maduro and Chávez ally, Rodríguez initially insisted that Maduro was Venezuela’s “only President” and accused the US of seeking to seize “our energy, mineral and natural resources”. However, she has since softened her statements, calling for a “balanced and respectful” relationship with the US.

One of the first actions taken by authorities was to order the release of over 600 opponents, union leaders, human rights activists, journalists and protesters who had been held for months. President of the National Assembly, Jorge Rodríguez, said that was done to “consolidate the peace of the Republic and peaceful coexistence”. Rodríguez has also announced the closure of El Helicoide – one of the headquarters of Venezuelan intelligence services. A detention centre both the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the United Nations Mission for Venezuela have described as a “torture centre” for dissenters is also set to be shut down.

Venezuela continues to face an ongoing US-imposed oil blockade that has disrupted exports of the country’s most valuable asset. The US has kept all the oil it seized from tankers. The blockade plays part of a campaign to pressure the Maduro government, including Rodríguez, to accede to the US’s demands. Trump further announced that Venezuela will be “turning over” 30-50 million barrels of “Sanctioned Oil” to the US worth around $2-3 billion. His intention is to sell the oil on the open market and ensure that proceeds benefit the interests of both Americans and Venezuelans. Trump has also posted that any revenue Venezuela makes from deals with the US can be used to purchase exclusively American-made products, meaning “Venezuela is committing to doing business with the United States of America as their principal partner”.

All this comes after Minister of Interior, Justice and Peace Diosdado Cabello’s announcement last December that, “not a drop of oil can leave here for the United States if they attack Venezuela. Not even half a drop can leave under any circumstances”.

Venezuelan authorities have also recognised that Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) is negotiating with the US for the sale of oil. Trump has moreover asked US oil companies to invest at least $100 billion to boost Venezuela’s production. However, companies, such as ExxonMobil have been reluctant to do so.

Former Minister of Communication Andrés Izarra has stated that Venezuela has now “stopped owning its oil no matter how you look at it. We retained normal ownership of the subsoil. But we lost control of who extracts it, how they extract it, to whom they sell it, at what price, under what jurisdiction, and what portion we have left as a Republic”.