It has become common for commentators on geopolitical conflict in the last twelve months to declare that ‘sea power is back’. There is a good reason for this. The world’s most contentious body of water is undoubtedly the South China Sea, where a growing cast of diverse nations are continuing to warm up the political temperature. s. Having festered for decades, The conflict over contested waters and islands in the region has festered for decades but the South China Sea became the focus of globally escalating naval tensions a few years ago when the Sino-American conflict ratcheted up in ferocity..

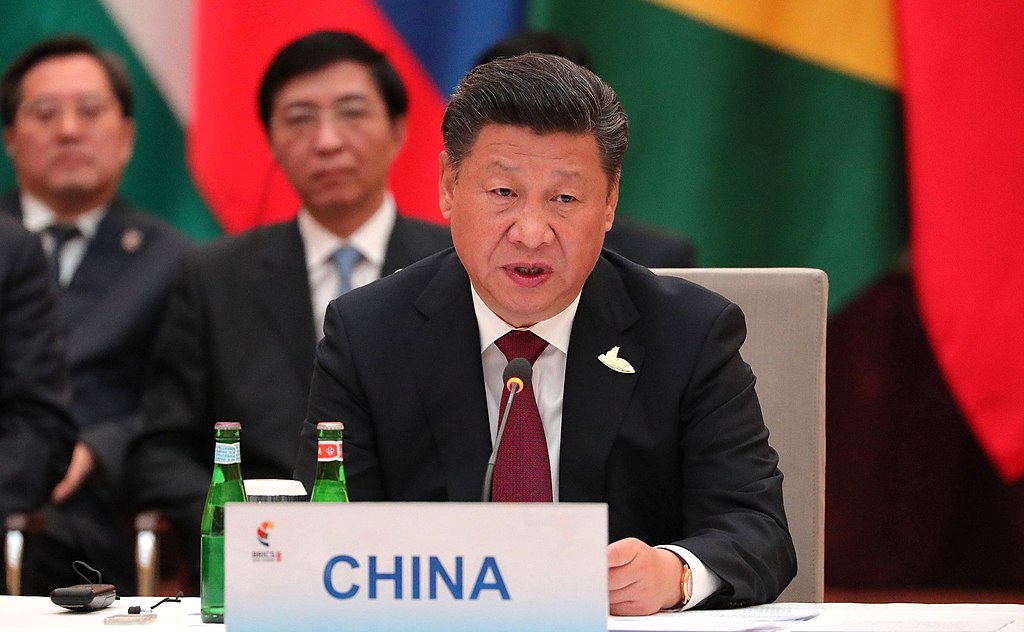

The longest-standing and most pernicious flashpoint in the South China Sea is between Taiwan and China. This stand-off has only intensified since the election of Lai Ching-te as Taiwan’s president in January 2024. China responded to Lai’s election for the first time in May with naval actions – large-scale military exercises involving the army, navy and air force around the island taken by Chiang Kai-shek in 1948. After Lai launched his presidency with a speech emphasising the nation’s identification as the Republic of China – something admitted by only a handful of nations worldwide – Chinese aggression has grown as expected.

The Media has estimated that the latest incursions are the closest that Chinese drills have come to the coast of Taiwan, although figures in Taiwan are equally keen to emphasise that the measures are not intended to provoke military confrontation. The latest Chinese moves in the area seem intended to stimulate and harass, but not necessarily to provoke.

The Philippines is perhaps the next major power in the South China Sea which is also increasingly implicated the region becomes more tense. The country has historically been aligned to the West, and to America in particular, but the leadership of Rodrigo Duterte from 2016 changed this. Up until two years ago, rapprochement with China seemed to be the destiny of one of South East Asia’s most underrated powers. Now, under the presidency of Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos, the Philippines has steered towards its traditional Western alignment at just the time when China has been stepping up its isolationist rhetoric and action in the region. Marcos’ repudiation of his predecessor’s policy is based on protecting national pride as well as a diplomatic realignment; throughout the six years of Duterte’s policy, China’s encroachments on Filipino waters and territories only increased. As with Taiwan, China’s strategy has been to harass aggressively, using particularly acerbic points of diplomatic conflict or peaks in the news cycle to target specific areas or naval convoys around islands of the Philippines. The Chinese aim is to provoke more fear than outright aggression in return, and to ensure that their continued encroachments begin to be normalised in the following years.

So far, many could say the Chinese approach has been successful. Despite Joe Biden’s strong talk on opposing aggression from the Chinese People’s Liberation Army and its Navy, there is scepticism in both the West and the East as to how coordinated or effective any American response could be. There has been continued friendly meetings with major figures in the Taiwanese independence movement and some provocative statements from leading American figures in the last two years. However,real military intervention to ward off Chinese ships seems unlikely under the present administration. The uncertain outcome of the next election will only play to China’s advantage while they wait to discover the nature of their foe after November this year. European navies are ‘paltry’ in comparison to those of the world’s major sea powers, and even with an increasing number of Asian being drawn into the centre of the South China Sea conflict, it seems unlikely that leaders such India’s Modi or Pakistan’s Sharif will be keen to go much nearer the fight.

The conflict in the South China Sea is as complex as it has been prolonged. Neither do its complexity nor its intensity show any sign of diminishing in the next half the decade. But its ramifications are becoming increasingly clear both to the American diplomats who care about the status of their nation’s role in the region, and to the regional leaders who recognise the growing worries of their neighbours about Chinese aggression. It is certainly true that a larger proportion of the region have swung towards America, or at least away from a peaceful relationship with China and towards a more stormy toleration. But this diplomatic change has been met only with increased vehemence in the Chinese claims for land and the regularity of Chinese military actions. The complexity and the longevity of this conflict show no sign of letting up. An acknowledgement of that fact should hit home with any of the national security advisors who wish to be returned to power in Washington later this year, and indeed anyone wishing to tread the testing and choppy waters of the South China Sea for the remainder of the decade.

Write for us!

Interested in writing for the OX1 column, looking for somewhere to turn your article idea into a reality? Then look no further. Both the Global Affairs and Environment Section are looking for new writers and contributors. If you’re interested in student journalism and want to get involved make sure to join the Oxford Blue writers group on Facebook.

Oxford Blue Writers Group:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/2462003647260904/?mibextid=oMANbw

Global Affairs Writers Group:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/441255647575456/?mibextid=oMANbw