In my childhood, being a Muslim meant that you were never a stranger. My family was Cameroonian, but I grew up feeling more connected to our Hausa tribe. I was surrounded by the blend of Nigerian and Ghanaian voices, where the borders of West Africa didn’t matter since the language of our parents and grandparents was what brought us together. I was raised on a version of Islam that existed as a unifying force, one where your character mattered above all. To me, the Muslim community was a home with no locked doors, a vast and expansive space that was free from the social exclusion I would come to experience in my daily life as a Black Muslim woman.

It was only as I grew up that I realised my vision of a borderless community stemmed from a child’s naivety. But how could I have known then that the sanctuary I loved was not a universal one—that it was often reliant on the silent exclusion of people who looked just like me?

When I was sixteen and visiting my family, my older brother came home and told me he couldn’t play football. It wasn’t because the pitch was full or shut down, but because the time wasn’t “ours.” This was in the south of France, and all I could feel was shock: there was a time for “les Arabes” to play, and a separate, later slot allocated for Black people, or “les Noirs.” This was no scandal; it was simply the way the locals operated. I was reminded of this incident during the holidays as I was walking alongside my brother on our way back from the supermarket. He pointed out a boy in the street—the same boy who had casually asked him if he thought he would “make a good slave.” A few days later, my brother saw that same boy at the local mosque for Jummah. They stood in the same line, perhaps shoulder to shoulder, in a house of God that apparently housed both the “master” and the “slave”—all without batting an eye.

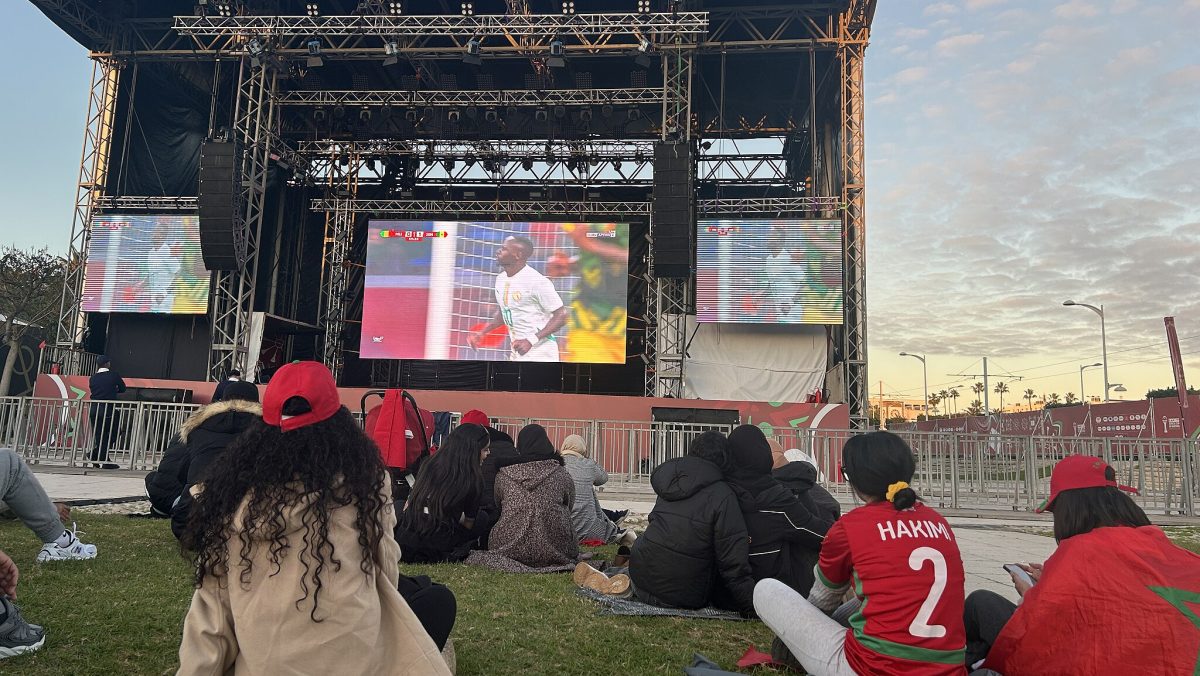

Reflecting on these moments, I realised that my brother’s experiences weren’t just “bad luck” or isolated, far-away incidents in the south of France; they were symptoms of a global and sobering reality. Anti-Blackness is so potent and pervasive that it does not respect borders. It seeps into every social space it touches—including the ones we hold sacred. This realisation stayed with me during the recent AFCON 2025 final between Senegal and Morocco. As it was my first time really following the tournament, I was just so caught up in the fun of it all. I remember thinking how exciting it was to see two Muslim-majority nations come out on top. The West African in me was leaning towards Senegal, but I was looking for celebration, not fighting. Yet, the discourse that followed the tumultuous match proved that even a game of football could incite a culture war. It exemplified how prominent anti-Black sentiment remains within the Ummah, leaving me to navigate the painful friction of having two core sides of my identity suddenly standing on opposite sides of a battlefield.

Without elucidating every detail of the match, the game had many tense moments: a disallowed goal in the 90th minute and a last-minute penalty that led to a flood of vitriol. While the general AFCON audience stood firmly behind Senegal, the story online told a different story. What should have been a celebration of a successful tournament—of Muslims succeeding alongside each other—quickly degraded into a tribalistic and racist battlefield. I watched mournfully as claims of a universal “brotherhood” dissolved into anti-Black tropes; accusations of witchcraft were hurled, and the Senegal team were labelled as “monkeys” and “disgraces.”

Even more frustrating was the “respectable” coverage from the likes of Sky and the BBC. Commentators branded the final “shameful,” suggesting Senegal should be disqualified for their brief walk-off in protest, twisting the narrative to favour Morocco under the guise of sportsmanship. In a tournament literally called the African Cup of Nations, the Blackness of the West African team was being weaponised against them by both their brothers and the Western lens. It became clear to me then that the solidarity we speak of in the mosque is often contingent; it is a contract easily repealed the moment a Black team dares to challenge the status quo.

But this isn’t just about sports. It would be a mistake to equivocate the vitriol of online supporters with the structural treatment of Black people across the North African and Arab world; yet, both are symptoms of a global architecture of extraction and erasure. I can see it in the silence surrounding the United Arab Emirate’s role in fuelling the genocide in Sudan, even as the UAE remains the country’s largest importer of gold. It is deeply disconcerting that this sobering tragedy can exist simultaneously with influencer-led campaigns that frame Dubai as a gleaming Muslim utopia.

This pattern of erasure resurfaced again with the controversy surrounding Marwa Atik, co-founder of Vela Hijab, after a picture of her posing next to the N-word was brought to light. The response from fellow Muslims online was telling: Black Muslims needed to “bury her sin” for the sake of unity. I’m starting to recognise this pattern for what it truly is: a one-way street of grace. We’re expected to show endless mercy towards the racism that undermines our very existence, while our fellow Muslims continue to profit from the violence and displacement of Black bodies.

But we cannot be asked for silence in the name of the Ummah, while those very same hands inflict our own suffering.

I look at the modern, Arab-centric lens of the Ummah and realise it ignores a much more beautiful and radical history. I recently learned about Florence Watts, an African-American who fled the terror of Jim Crow laws for Chicago. It was there, in 1922, that she officially accepted Islam through the Ahmadiyya Movement, adopting the new name ‘Zeineb’. Her conversion was an act of agency—a recovery of ancestral history that was disrupted by slavery. For Florence, or Zeineb, Islam offered a global community rooted in liberation; it was rebellion. It was a tool of revolution used to reclaim a humanity that White supremacy tried so hard to steal from her. This is the Islam I recognise. It’s the one that exists in the heart of my British Hausa community, spanning cultures from Benin to Niger, proving that our faith doesn’t depend on our submission to someone else’s ethnic hierarchy.

This piece barely touches the surface of my experience—let alone the experience of the Black Muslim collective. My intersecting identities have shaped every facet of my life; they have raised me to navigate a world that sees me as a spectacle or a talking point or a statistic before it sees me as a person. But I no longer find them to be a burden; they are the core of who I am. I think I’m ultimately writing this as a reminder that we are just as much members of the Ummah as any other ethnic group.

This is a lamentation of how far we have strayed. We have failed to combat societies that have allowed anti-Blackness to become entrenched, ignoring the very verse that tells us we were made into tribes and nations so that we may learn from one another—not so one could lord over the other. If our “brotherhood” is so fragile that it cannot survive the presence of Black sovereignty, then it is hardly a brotherhood at all.

It is simply another system of oppression dressed in the clothes of the sacred.