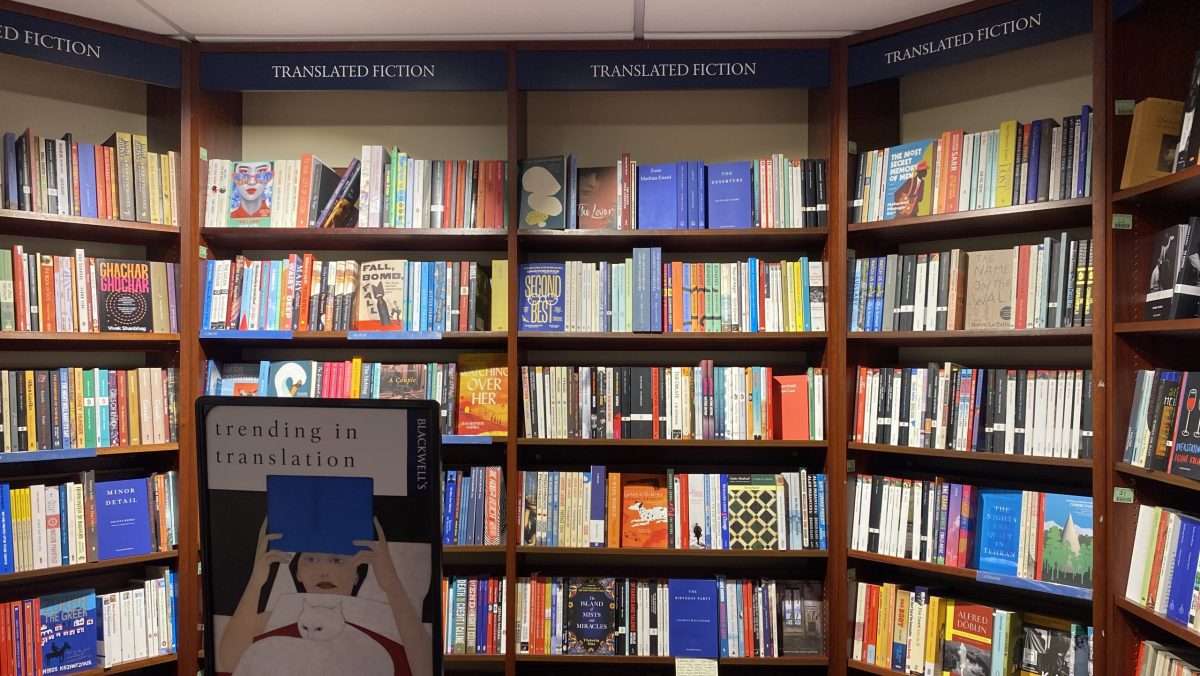

My Saturday mornings consist largely of one poorly timed wakeup, two scalding coffees, three minutes late to my weekly Oxford Blue meeting, and four more books purchased in Blackwell’s on the journey home. Each time I make the fateful £45 decision to walk through that door, I find myself drawn specifically to the ‘Translated Fiction’ section on the first floor. A section so beguiling I metamorphose into a voracious magpie, in awe of the dazzling titles and shiny covers. I am by no means alone in my fascination: a recent survey conducted by Nielsen for the Booker Prize Foundation highlights that young people drive the sales of translated fiction, despite the largest group of readers being over the age of 60. Recently, I have started to wonder if the segregation of translated fiction from works originally composed in English may be problematic, despite its convenience. Does the separation of translated works simply acknowledge the painstaking and vital work of the translators involved? The notion that works of fiction not originally written in English, and thus ideas not originally pondered in English, are in some way inherently different or perhaps second-fiddle is most certainly a dangerous one.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, more commonly known as the theory of linguistic relativity, posits that the language that we speak is related to, and influences, the way we think. Deservedly, this theory has come under great scrutiny since its inception. Originating from the assumption that Native American people were inferior in their grammatical structure, and therefore their cognition, this hypothesis is rooted in colonialism. American linguist William Dwight Whitney went as far to state that Native American languages must be eradicated, and that those who spoke them should be taught English in order to adopt a ‘civilized’ way of life. In this case, the implication that thought differs with language fosters nothing more than bigotry. However, contemporary cognitive scientists and linguistic philosophers alike have accepted a slightly more palatable form of the theory of linguistic relativity: that language reciprocally influences thought. For instance, in his elementary works, Whorf himself discovered that in the Inuit lexicon, there are three words to distinguish varieties of snow, enabling increased perceptual discrimination between types of snow in Inuit communities. This is an example of a lexical gap, as a direct translation of such terms does not exist in English.To put it plainly, native English speakers simply do not need three words for snow. French and Czech author Milan Kundera, known for his groundbreaking novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, emphasises the issues that lexical gaps breed for translators. The Czech word ‘litost’ has no exact translation in any other language, yet Kundera cannot “see how anyone can understand the human soul without”. The term depicts a feeling “as infinite as an open accordion, a synthesis of grief, sympathy, remorse, and indefinable longing”, which begs the question – does the language in which we read a novel change the emotions it evokes? And, if this is truly the case, does translating a piece of literature from its mother tongue dampen its effect?

One of my personal favourite examples of translated literature is the work of Olga Tokarczuk, a Nobel Prize-winning Polish author whose literary activism is laced with what can only be described as magical realism. Antonia Lloyd-Jones, who has translated many of Tokarczuk’s works into English, shared her experience with translating in an interview with Notes from Poland. Lloyd-Jones admits that “it is difficult not to get seduced by the Polish text and stick too closely to what’s on the page”, and expresses the need to consider “if this person were writing in English, how would they write that?”. The role of the translator is ultimately not to reproduce, but to allow each and every individual to best reap the benefits of the abundant harvest of literature worldwide, maintaining both connotation and denotation

Translated fiction is a vehicle for literary travel across borders, facilitating visits to the best tourist attractions and recreational indulgence in some of the intimate aspects of different cultures. It is not a pair of magic glasses that enables us to see the world from another perspective. Our digestion of translated fiction is inevitably compromised by our backgrounds and past experiences, but this does not take away from its merit as a window into the life of another. We will never know what it is like to think in another first language, just as we will never know what it’s like to grow up somewhere else. In an International Booker Prize interview, Vigdis Hjorth, author of Is Mother Dead, says that reading translated fiction is important because:

“reading fiction from abroad, but in your own language, is a meeting with experiences, environments and cultures that are different from your own, but still you met them in a way that is familiar, in your own language. It’s a win-win experience”.

The way we think is most certainly impacted by the culture in which we are embedded, which inevitably includes our native language. Thus, the creative labour of the translator in preserving the intentions of the author, whilst appealing to a dissimilar cultural demographic, is not one to be overlooked. To acknowledge that a piece is translated is to acknowledge our ignorance of it in its true context, but appreciate the invaluable insight it gives us. Whilst the emotions aroused when reading a book in English might not be the same as those experienced when reading it in its original form, it is the closest we can come to literary universality, to broadening our horizons in the comfort of our own homes, and to embracing our unrelenting curiosity. Completely incomparable, translated fiction cannot be dictated as better or worse than its originally English counterpart; it is a necessary piece of the puzzle depicting humankind. We should all engage with it, but not with the expectation that it is a perfect representation of the initial version in its true context.