Trigger warnings: I, Medusa involves themes of sexual violence, racism, and domestic violence

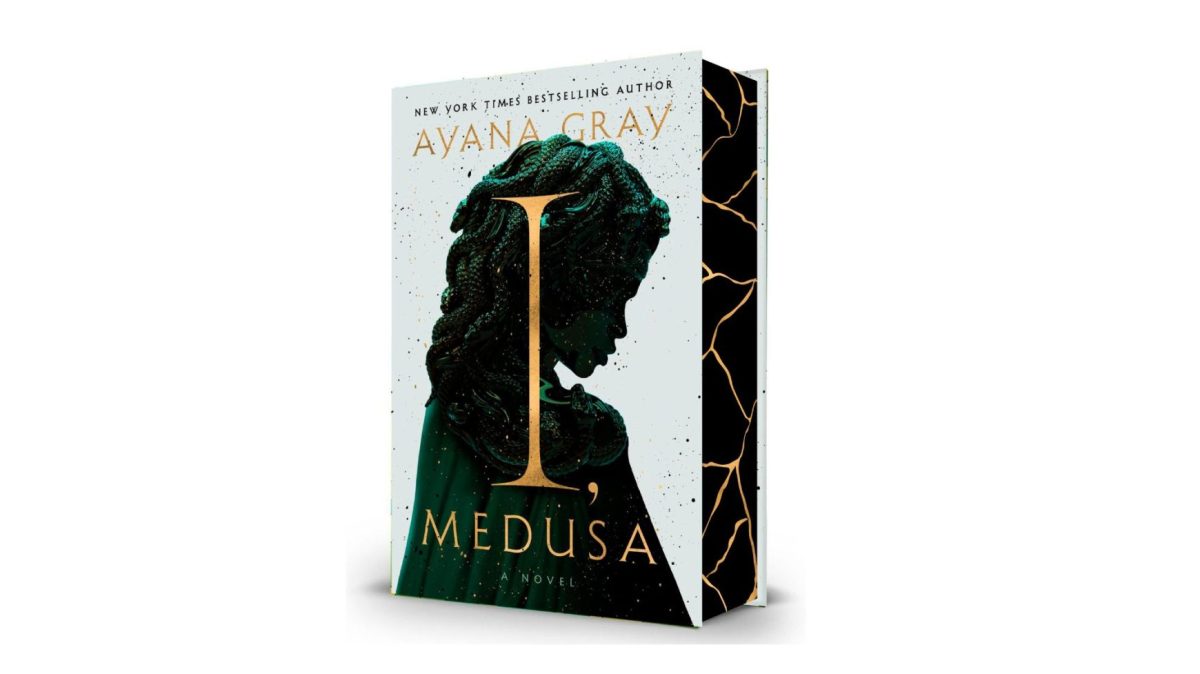

The last decade has seen a boom in retellings of Greek mythology, where authors centre the sidelined female voices of a predominantly male canon. Circe, The Silence of the Girls, and A Thousand Ships are just a few of the novels in this genre which I have enjoyed. I, Medusa, by the NYT best-selling author Ayana Gray, ranks comfortably among them. Gray brings sidelined voices to the fore by centring black pride, and if you’re a keen reader of retold Greek mythology, I would recommend adding Gray’s novel to your list.

In the interest of transparency, a Penguin Random House publicist sent me an advance readers’ edition of this book for free, in exchange for an honest review before its official release on the 18th of November this year. Happily, this review will be honest and (largely) positive. I, Medusa is a solid piece of adult fiction.

In this novel, Gray explores one of the most famous monsters in Greek mythology – the Gorgon Medusa. You probably know her as a hideous villain with snakes for hair, beheaded by Perseus, and possessing a lethal gaze which turns everyone to stone. In I, Medusa, however, you will get to know Meddy, the seventeen-year-old granddaughter of the primordial goddess Gaia – an ambitious teenager desperate to leave her violent parents’ island and become a priestess of Athena. This is her villain origin story (perhaps).

In her retelling of the story of the Gorgon Medusa, Gray does not shrink from the darker side of the myth. Book IV of Ovid’s Metamorphoses offers one of the most famous depictions of Medusa. In Ovid’s poem, the god Neptune (Poseidon) raped Medusa in the goddess Minerva’s (Athena’s) temple, and the goddess consequently turned Medusa into a hideous monster. In popular culture today, the figure of Medusa is often used as a symbol of surviving sexual violence, with the Medusa tattoo being a particular example of this.

Whilst I, Medusa is a thoroughly gripping read (I finished it in a day), the book’s opening scene, which tackles the theme of sexual abuse by a trusted authority figure, almost made me put it right back down again. On the whole, Gray is fairly non-graphic in her descriptions but if you are sensitive to depictions of sexual violence in media, I would recommend reading Gray’s novel with caution.

What makes I, Medusa simultaneously effective and frustrating is how cruel most of its characters are. Yes, there are some characters who have the dubious honour of being truly awful standouts but, as a rule of thumb, if a character exists and has any degree of power, they will inevitably inflict violence on others. The power afforded to men in the patriarchal society of Ancient Greece means, consequently, that almost every man in I, Medusa is a dreadful person. Meddy’s best friend Theo is the exception to the line of terrible men in I, Medusa – kind, supportive, and full of integrity – but he is also enslaved and thus lacks practical agency.

The women of I, Medusa follow this same pattern. The more power they have, the more violence they assert against characters who have less agency. Athena, who is threatened by Poseidon, in turn inflicts violence against those less powerful than she is. Likewise, as Meddy progresses through her journey as an acolyte (priestess-in-training) of Athena, she steadily becomes more prone to acts of brutality, first attacking a child, then a fellow acolyte, then a soldier of Athens. Thus, Gray repeatedly draws attention to the corrupting nature of absolute power. Whilst this makes for an occasionally dispiriting read, Gray does effectively demonstrate the cyclical nature of systemic violence. Meddy’s father – banished by the gods – inflicts violence on Meddy’s mother, who in turn inflicts violence on Meddy and her sisters.

Aside from the theme of domestic violence, Gray also presents Meddy’s experience of racism and microaggressions at the hands of the other acolytes in Athena’s temple. Gray effectively demonstrates how Meddy is made doubly vulnerable to violence through the intersections of her race and gender. However, the novel is also a joyous exploration of black pride, and Gray’s portrayal of race in I, Medusa is a standout part of the novel. Key bonding moments between Meddy and her sisters (Stheno and Euryale, the other two Gorgons in Greek mythology) occur while Meddy’s sisters are braiding her locs. Moreover, Meddy offers hair braiding as her craft to Athena’s high priestess, a skill which enables her to pass the second round of tests for the acolytes. Meddy’s pride in her hair also makes her ultimate fate and transformation all the more devastating.

These moments of black joy and pride are, however, far and few between, continuously overshadowed by the persistent, ever-shifting forms of sexual violence in the novel. Gray avoids being gratuitously graphic, but the repeated depiction of sexual abuse throughout the book does make I, Medusa a heavy read. However, Gray does an effective job at highlighting the different forms sexual violence can take – whether from a group of strangers, a trusted authority figure, or even a lover. Crucially, Meddy is attracted to Poseidon as they interact throughout the novel. She just doesn’t want to have sex with him. The scene after Poseidon rapes her in Athena’s temple is a masterclass in the dangers of victim-blaming, and Gray’s sensitive handling of this topic – and the wider topic of sexual violence – is laudable.

Although Meddy’s initial attraction to Poseidon enables Gray to give a sensitive depiction of sexual abuse by a predator, it also exposes a significant flaw in the book. The contrast between the paragraphs dedicated to swooning over Poseidon and the half-page setup of (frankly, almost non-existent) homoerotic tension with the friend who will eventually become Meddy’s lover is as stark as it is disappointing.

The single scene which sets up the relationship with Meddy and Apollonia displays a sorry lack of yearning. Gray sets up this alleged ‘homoerotic tension’ in almost a single line: “my heart is still thundering, but now I’m less sure if that’s a consequence of our dancing or of the way Apollonia’s palm felt pressed against mine.”

In contrast to this, from the moment she meets Poseidon, Meddy consistently contemplates how much she is drawn to him. Just a few examples include: “I feel as though someone has let loose a hundred hummingbirds inside my chest”; “My heart beats wild and frantic in my chest, and some part of me wonders if it’s possible to forget how to breathe”; and “he looks at me, and I’m convinced that nothing in all the world has ever been more beautiful than he.” In Meddy’s most egregious comparison of Poseidon and Apollonia, she notes: “it is similar to how I felt when I was dancing with Apollonia earlier, but better.”

My problem with Gray’s representation of Meddy’s feelings for Poseidon and Apollonia is that it plays into the stereotype so often confronting bisexual/queer women: that their feelings for women are somehow less valid than those for men. It’s particularly galling in this instance, as Poseidon is clearly portrayed as a predator and yet for most of the novel, he is far more romanticised in Meddy’s eyes than Apollonia is. I do think Gray made an effective choice in demonstrating Meddy’s attraction to Poseidon because this ties into the broader points the author makes about abuse, and her demonstration of how predators can operate. In Meddy’s mother’s words: “that’s the curious thing about monsters […] The worst ones don’t bother hiding in the dark.”

However, such a gaping chasm stretches between the portrayals of Meddy’s feelings towards Apollonia and Poseidon that it just does not sit right. Whilst I appreciate that Gray was aiming for positive representation, here is one of the few places where I feel she really missed the mark, and instead played into tired stereotypes about queer/bisexual women. Bisexual representation – which involves Meddy having far more romantic tension with her rapist than with her actual lover – is, at best, incredibly shoddy and, at worst, barely merits the term.

Despite its flaws, however, I, Medusa is a compelling read which navigates a variety of heavy topics with sensitivity and empathy. If you’re a fan of retold Greek mythology, I would recommend keeping an eye out for its release on 18 November 2025.