Lola Dunton-Milenkovic

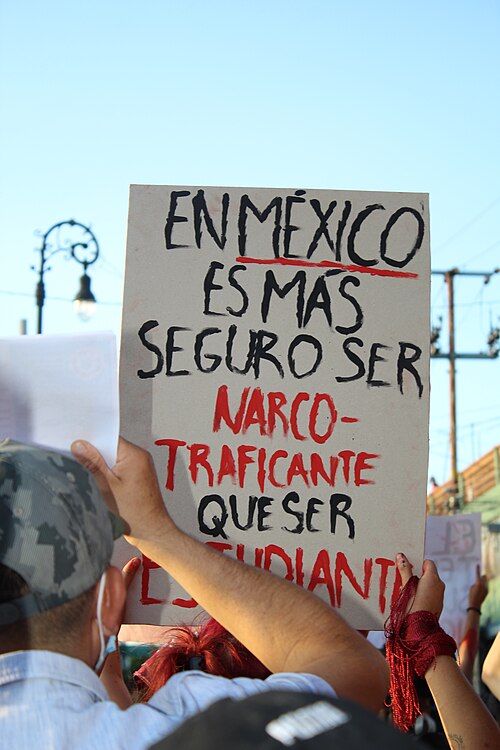

On 15 November, protestors took to the streets in cities across Mexico to express frustration with Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum’s handling of corruption and drug violence, which claim tens of thousands of lives in the country each year.

The protests were led by a group labelling itself Generation Z Mexico. Prior to the protests, the group circulated a manifesto on social media describing how young Mexicans are fed up with violence, corruption and abuse of power. Although labelled as part of a global Generation Z movement, the demonstrations included retirees and youth alike.

The protests spread across more than 50 cities and left at least 120 people injured. Its popularity is evident of widespread frustration throughout Mexican society, and indeed the movement “represents no single thing; it’s about everything: injustice, insecurity, the disappeared, the lack of education, the lack of employment. It’s a discontent with how the country is being run,” as voiced by 18-year-old student Jacobo Alejandro.

The Mexican government, however, is claiming that the protests were organised by right-leaning politicians and businessmen, and promoted by bots on social media. Sheinbaum’s administration described the protests as part of an “inorganic, paid” campaign organised by her opponents. A government press conference also traced their online promotion to opposition-linked figures and newly created social media accounts, a strategy officials assert cost nearly $5 million.

What happened at the protests?

Rallies took place in dozens of cities, from Tijuana in the north to Oaxaca in the south. They drew large crowds, with some demonstrators carrying the pirate flag from Japanese anime One Piece, which has become a global symbol of the youth movement. The black flag bears a skull with a straw hat, and is carried by a rowdy crew of pirates in the series whose mission is to challenge a draconian regime and fight for freedom.

Demonstrations in Mexico City’s Zócalo plaza began peacefully but descended into violence, with protestors pelting riot police with rocks. Officers retaliated with batons and fire extinguishers. By the evening, protestors had torn down some of the metal fences surrounding the National Palace where Sheinbaum lives. A tense face-off between masked protestors and police guards escalated when clouds of tear gas covered the scene.

The security chief of Mexico City claimed that, “for many hours, this mobilisation proceeded and developed peacefully, until a group of hooded individuals began to commit acts of violence.” He added that 100 police officers were injured, 40 of whom required hospital treatment, while 20 protestors were hurt.

Footage of riot police violently kicking and punching protestors, however, has also spread on social media. Víctor Camacho, photographer for one of Mexico’s main left-wing newspapers La Jornada, accused the police of assaulting him as he covered the rally. The newspaper wrote that, “although [Camacho] identified himself as a newspaper photographer, he was kicked, insulted and threatened, and two police officers stole his photographic equipment and his phone.”

There were also reports of disturbances in Mexico’s second-largest city, Guadalajara. According to authorities, 47 people were detained and 13 people were injured, including three police officers.

What caused the protests?

The protests were caused by the longstanding issue of organised crime. Despite Sheinbaum’s efforts to tackle the problem, many Mexicans feel that murder and corruption maintain a powerful hold over their lives.

Mexico has indeed been facing a crisis of criminal violence that has left over 30,000 people dead each year since 2018. It stems from both gangs and drug cartels, as well as the state which has committed human rights violations against these groups. Extortion remains at an all-time high, and some states have become battlegrounds for cartels equipped with military-grade weaponry.

A particular horror is Mexico’s forcible disappearances, marked every year on 26 September by an annual march. It commemorates the forced disappearance of 43 male students in Ayotzinapa in 2014. These students are just the most high-profile among thousands of victims. They disappeared from a rural teachers’ college at the hands of a crime faction working with local and federal authorities. Family members from Monterrey to Mérida continue to arrive annually in Mexico City to march, begging for help in this unsolved case to find their missing loved ones.

The lack of closure serves as a constant reminder of a crisis that has engulfed the nation. More than 100,000 people have disappeared in Mexico since 1964. This stems from a combination of soaring cartel violence and government impunity, leaving tens of thousands victims unaccounted for, many dead and buried in unmarked graves, others kidnapped and forced to work in organised crime.

Sheinbaum is Mexico’s first female and first Jewish president. She served as mayor of Mexico City from 2018 to 2023, coming into the Presidency in October 2024 as a candidate for the National Regeneration Movement with a landslide victory. She remains widely popular, and the opposition remains disorganised. However, although Sheinbaum’s approval ratings remain above 70%, she has faced criticism over her security policy following several high-profile murders.

One of the murders looming over the protests, as many demonstrators waved white flags or wore cowboy hats, was that of Carlos Manzo. Mayor of Uruapan in the state of Michoacán, he led a crusade against drug trafficking in his town and called for a crackdown on criminality. He was known for speaking openly about drug-trafficking gangs and cartel violence, and demanding tough action against cartel members who terrorise the country.

Manzo started an independent political initiative known as the Sombrero Movement, and clashed with Sheinbaum over her security strategy, which he believed was flawed and ineffective. He called for an iron fist approach to crime, even announcing that he would reward police officers who killed cartel hit men. Manzo was assassinated on 1 November during Day of the Dead festivities.

Is it all as it seems?

The protests mark part of a broader global wave of youth-led, anti-corruption movements wherein young people are mobilising against systemic corruption, inequality, and impunity. These started in Indonesia and Nepal, and have since spread to the Philippines, Morocco, Madagascar, Togo, and Peru.

Yet the protests in Mexico drew participants of all ages, whose ideas remain divided, arguably making them ineffective as an opposition. They started off as an anti-violence movement led by Mexican youth, with its original viewpoint evident in a statement by 19-year-old Omar Cortés: “We’re obviously not going to achieve [Scheinbaum’s resignation], because that’s too extreme. But it’s about letting the government know that we’re willing to go that far. Because when those at the bottom move, those at the top fall.”

The demonstrations are now sown with confusion, with many older participants calling for the toppling of Sheinbaum and intervention from the United States. This includes actor and singer Rodrigo Santana, who voiced his sentiments: “I’m tired and saddened by the situation in the country today. The goal of this march is to remove the president from office. And to show that we are angry, that the people are not with her.”

Even the supposed banding together against violence following the murder of Manzo is laden with suspicion. A large banner on the barricades protecting the Angel of Independence monument memorialised the mayor by comparing him to El Salvador’s right-wing president, Nayib Bukele, with a slogan: “They took away our Mexican Bukele, Carlos Manzo, to scare us. But they gave us a national hero.”

Bukele is infamous, lauded for his aggressive anti-gang policies, while simultaneously systematically undermining El Salvador’s democratic institutions. By comparing Manzo to Bukele, strong right-wing messages are being sent. This is also reflected in the similarities between Manzo’s approach to US President Donald Trump’s attitude to drug trafficking and gang violence. Manzo advocated for the killing of cartel hitmen, and similarly Trump has said: “Would I launch strikes in Mexico to stop drugs? It’s OK with me.”

Sheinbaum is adamant that the protests were infiltrated by right-wing politicians and business leaders that oppose her government. There is an argument that only the United States can loosen the cartels’ grip, whereas Sheinbaum has repeatedly opposed the idea. She stresses that while her government cooperates with US authorities on intelligence sharing, any foreign security operation on Mexican territory would violate its sovereignty.

During a daily news conference from the presidential palace, Sheinbaum stated that the demonstrations were promoted on social media by 8 million bots operating from outside the country. An analysis by Infodemia, an official fact-checking agency tasked with combating ‘fake news’ targeting the government, also showed that key sponsors of the march include billionaire Ricardo Salinas Pliego (Mexico’s third richest man), former President Vicente Fox (of the opposing conservative National Action Party), and businessman Claudio X. Gonzalez. Leaders from the opposition National Revolutionary Party, and National Action Party, likewise supported the protests.

The situation in Mexico remains unclear and uncertain. The only real conclusion that can be made is that these protests have tapped into powerful anti-corruption and anti-violence sentiments. Whether they evolve into something much more politically motivated remains to be proven. Yet the growing reports of external interference and suspicious funding indicate that there might be something lurking in the shadows.