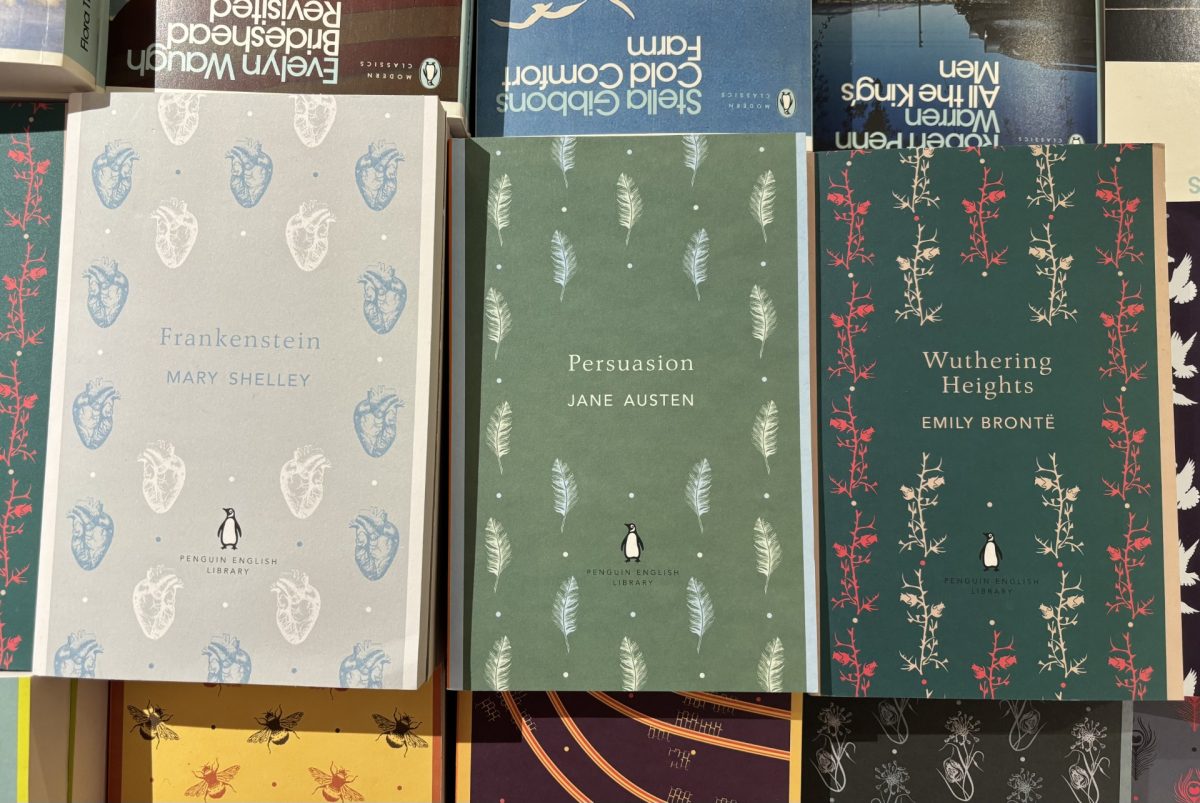

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein was the novel of my early teenage years. My first copy was a present for my thirteenth birthday; a paperback in pastel blue, the front cover adorned with anatomical hearts. After reading it, I would declare to anyone who would listen that Frankenstein was my favourite book, gobble up every autobiographical detail about Shelley that I could get my hands on, and weasel hearts and lightning bolts into as much of my work at the local art club as I could get away with. In hindsight, I was quite insufferable about it all, although I was right about the book being great.

It was out of this childhood love for all things Frankenstein that, when I logged onto Letterboxd to review Guillermo del Toro’s new film adaptation, I drew a complete blank. I changed the number of stars that I gave it at least twice. The ‘review’ that I wrote was jumbled, indecisive, and comprised of more questions than opinions. In fact, it still is (even after a rewatch and several weeks worth of consideration). My issue with Del Toro’s Frankenstein is not that it is a bad film, far from it, but that it is simply not the Frankenstein that I know and love. My heart was torn between admiration for Del Toro’s ability to craft a fantastical world with such skill and attention to detail, and a sense of loyalty to Mary Shelley herself.

I stand by my original impression that Del Toro’s Frankenstein is a good film. I found that the costumes, set design, and acting were good at the very least, sometimes even great. I regret not having gone to see it at the cinema. The film’s visuals aren’t making up for a lack of substance, either: Del Toro’s Frankenstein grapples with a great number of themes ranging from otherness and isolation to faith and family ties, all of which are present in the original source material. In the 45 minute production documentary which Netflix released alongside the film, the cast and crew describe how Del Toro was involved with even the most minute details. As both director and writer behind the project, he describes how he made an effort to translate Mary Shelley’s themes and writing style in the book across to his script, even as he changed key plot details. This would explain why I felt that the film chimed thematically with Shelley’s novel, although Del Toro clearly prioritises certain ideas over others.

Frankenstein (2025) is predominantly a film about the relationship between fathers and sons. Although I would not say that this is the core theme of the book, there is a tenderness in this portrayal that is often rather moving and I think brings a new, but significant, lens through which to view Shelley’s classic. The way that Victor flits between being a victim of his father’s apathy and an abuser of his power over the Monster is disturbing. It is equally upsetting to watch the Monster as he endeavours to find love, particularly paternal love, in a world that is almost unanimously and entirely unfairly prejudiced against him. As a film about paternal relationships, it works.

My issue is that Del Toro strays so far from Shelley’s novel that it becomes almost unrecognisable about an hour in – aside from the arrogant-scientist-brings-corpse-back-to-life of it all. Victor Frankenstein? Vaguely recognisable, though significantly older and with a worse relationship with his family. Elizabeth? Again, vaguely recognisable – if you squint. William Frankenstein? Forget it. The relationships between all of the characters have been warped so greatly from their original form in Del Toro’s script that the film itself starts to resemble the ship of Theseus. Is it still Frankenstein if almost everything about it is different to what Mary Shelley envisioned? To what she achieved? Del Toro also makes reference to Percy Shelley’s Ozymandias within the film itself and wraps everything up at the end with a quote by Lord Byron. To put it lightly, a strange choice for a film which adapts arguably the first science-fiction novel, written by a teenage girl. Watching the documentary makes these choices seem even stranger. Del Toro’s discernable adoration for Mary Shelley’s novel does not easily chime with his decision to adapt it so unfaithfully, nor to honour the men who surrounded Shelley in life more conspicuously than the author herself.

So, a good film and a bad adaptation. Does being a bad adaptation undermine being a good film? Should it? Sitting on my bedroom floor with the Letterboxd app open on my phone, I grappled with this conundrum. My entire review hinged on how much I decided that a film, or any adaptation for that matter, owes to its source material.

I think a film that is both a bad adaptation and a bad film is required to consider this further. Persuasion (2022), starring Dakota Johnson, does not work on any level. Although the cinematography is pleasant and there is the odd good performance, the film is frustratingly intent upon delivering every plot point with a knowing look and a line filled with internet buzzwords. I do not want to be subjected to the phrase “I’m an empath” in an Austen adaptation. The film lacks all charm because it attempts to be both a semi-accurate adaptation, given that it is a regency period drama, and a modernisation. Because Austen’s place in the literary canon is in no small part due to the enduring nature of her humour and depiction of human relationships, the nods to the 21st century feel forced and unnecessary. We are clever enough to see how a period piece can be relevant to the modern day without having it thrown in our faces.

This is something which Clueless (1995) – an adaptation of Austen’s Emma – understood far better. Clueless does not pretend to be an accurate adaptation of Emma and instead embraces the themes in Austen’s novel, translating them into a more modern setting and thus adapting Austen’s key ideas for a new audience. Thus, it is able to be both a good film and a good adaptation. Persuasion, on the other hand, sheds everything but the basic plot and in doing so it becomes a film lacking any substance as an adaptation, a film that understands neither Austen nor its audience.

So where does Del Toro’s Frankenstein stand in all of this? Like Clueless, it upholds many key themes from its source material, even if its priorities are different. Like Persuasion, it constructs a world which is too similar to the original source material to get away with making such significant changes and keeping the original text’s name. The film’s main problem is perhaps that it is called Frankenstein whilst quite obviously not being Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Perhaps it is in taking Shelley’s title without also taking all of the plot points, characters, and ideas that come with it that Del Toro has provoked the ire of her admirers.

Del Toro had the opportunity to signal through his title that this would be a film adaptation which had taken liberties, but he chose not to. The posters for Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights (2026) place the title in quotation marks – a signpost that the film will not be a faithful adaptation, although the decision to cast Jacob Elordi as Heathcliff (a choice that has proven controversial) indicated this anyway. I do not particularly want to discuss Fennell’s film in any depth before it comes out this February. Currently, I am unimpressed. There’s a chance that I will be proven wrong – we will see. In any case, the stylisation of the title does at least confess an unwillingness to adapt Brontё’s source material accurately. On some level, I think this honesty is a good thing. It makes the audience more aware of the fact that what they are going to watch will be an adaptation and should, therefore, be considered as at least partially distinct from the novel. I wonder if my difficulties with Del Toro’s film would be so severe if it had been titled “Frankenstein” instead.

Del Toro’s decision to give his work the original title means that there is no clear demarcation between novel and film: they are thus inevitably and inexorably bound together and I cannot honestly consider his work as something independent. The film stands on Mary Shelley’s shoulders but never really thanks her for the effort. It glances down at her once or twice, then quickly looks off at something else.

I could not say whether Shelley would think of this as an act of ingratitude or an inevitability of the process of adaptation. As I sat scrolling through Letterboxd reviews, I oscillated between the two. I lean now towards the latter, willing to accept that ideas and perspectives may be lost through adaptation, but also gained. And how badly has a good story ever been hurt by a new storyteller? Perhaps I will eventually swing back in the other direction. Ask me in February.