Labyrinth Productions’ production of A View from the Bridge kept me on a knife’s edge.

Of all the great American dramatists of the 20th Century, Arthur Miller is perhaps the most attuned to the art of building tension. He expertly crafts characters with hidden insecurities and illicit longings, unsaid yet powerful emotions that keep bubbling under the surface over the course of a play – finding their release, ultimately, in tragic annihilation. A View from the Bridge is one of his greatest plays (Death of a Salesman withstanding) – and arguably, his most tense. But director Rosie Morgan-Males has proven herself highly adept in capturing the nuances of the Millerian style in her interpretation of the play. She successfully makes that tension feel palpable, sharp, and electric, from beginning to end.

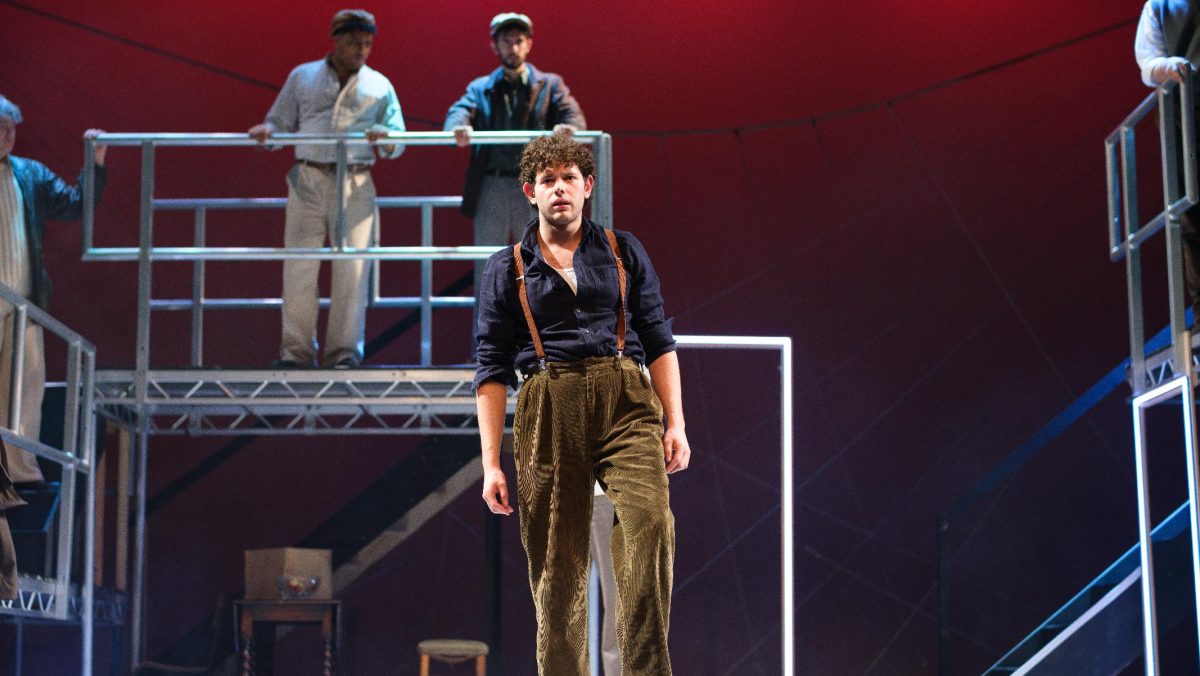

A View relates the fall of Eddie Carbone (played by the endlessly talented Nathaniel Wintraub), a longshoreman and a family man who lives by the titular Brooklyn Bridge with his wife Beatrice (Rose Hemon Martin) and his niece Catherine (Catherine Claire). But when Beatrice’s cousins, Marco (Gilon Fox) and Rodolpho (Robert Wolfreys) immigrate from Italy, and plan to make a new life for themselves in the States, Eddie finds his status quo irrevocably shaken – especially when Rodolpho begins to make a move on his niece. Amidst this, Eddie grapples with his strong feelings of honour, anxiety, and a rather perverse desire…

This play does a fantastic job of immersing us in the period, opening with a slideshow of a series of photographs from New York in the 1950s. Accompanied by a stirring soundtrack, and the earthy noises of people and traffic in the bustling metropolis, it powerfully conveyed the sheer grit of the play’s setting. Following this broad-brush portrait of the city, the screen lifts to reveal the Carbone apartment, adorned quite humbly with a dinner table, a few chairs, and a record-player. As the play nears its calamitous final moments, even this meagre display gets stripped down, pared away into a blank space: by privileging sparsity, the play allows the emotional force of its characters to take centre stage.

And if we want to speak about the emotionality of Morgan-Males’s production, we would be amiss to ignore its driving force: Wintraub’s Eddie. At the start of the play, he is both the centre of gravity of his household and of his community. Wintraub does a fantastic job of striking the delicate balance of Eddie’s hypermasculine self-assurance and his ever-gnawing insecurities, especially once his Italian relatives enter onto the stage. His performance was at its most gripping whenever his mask of calm briefly slipped off; the audience becomes sensitive to such moments where he raised his voice, or leapt up from his chair to berate Wolfreys’s Rodolpho, the ominous forebodings of the absolute wreck of a human he becomes by the play’s second act. In his performance of our tragic protagonist, Wintraub fiercely portrays a man with (as the narrator Alfieri puts it) “too much love” – a man of excess and passion in its etymological sense of “suffering”. In Act II, a passionate kiss simultaneously becomes an act of strangulation: this moment to me embodied the essence of Eddie’s character, as Wintraub successfully toed that razor-thin line between excessive desire and excessive violence that drives the play’s tragedy.

Of course, this is not at all to devalue the performances of our other leading actors. We are only made so hyper-sensitive to Wintraub’s flashes of emotion purely because of the conduct of the characters around him. We empathise with Hemon Martin’s performance as the put-upon housewife, and share in her sheer desperation whenever Eddie loses his calm, and the harmony of the Carbone household begins to be thrown off-kilter. Similarly, Claire’s performance of Catherine beautifully conveys that universal longing for freedom, independence, and maturity – in her case, must contend with a suffocating uncle in order to attain this. Claire unravels Catherine’s layers; the innocence and naivety gives way to confidence and a voice over the course of the two Acts, and it is genuinely refreshing to see her confront her uncle during the play’s final scene, once Eddie does the unspeakable.

Wolfrey’s Rodolpho and Fox’s Marco also gave beautiful performances. Through his stoicism and machismo, Fox embodied everything that Eddie wished to be: he does not need outbursts to be a source of tension in the play, as his silences speak louder than his words. Wolfrey, meanwhile, imbued Rodolpho with a natural magnetism and buoyancy that leaves no doubt as to how Eddie becomes so insecure. He is a refreshing foil to the raw brutalities of the play, and I was endlessly charmed by his humour and wit; rather than playing Rodolpho up to be an annoyance in the way that Eddie sees him, Wolfrey exudes charisma, and I felt more anxious for him than anyone else whenever his character and Wintraub’s inevitably clashed.

However, my personal favourite character performance was Alice Wyles’s Alfieri, a character who deserves far more airtime than my review has allowed her thus far. Wyles’s Alfieri – our narrator, and our one-man Grecian chorus – represents the voice of reason in a space overwhelmed by big personalities with excessive emotions. His constant recourse to “the law” – which he sees as essential, inviolable, just – clashes with the vigilante justice which our leading characters attempt to bring to the table. It is Wyles that has the first and last words of the play, and her conveyance of Alfieri’s infinite wisdom allows the tragedy’s more humane messages to breathe underneath all of the blood and lust.

I should also briefly mention that it was a joy to see familiar faces – seasoned OUDS veterans, as it were – perform alongside the Freshers who had the opportunity to debut in a space as prestigious as the Playhouse. I look forward to seeing what places they go to next – and, likewise, further efforts from the community to inject fresh new blood into Oxford’s dramatic scene.

If I had to give a single criticism to an otherwise very strong production, it would unfortunately have to be its use of music. The live orchestra was a very useful way of mediating the audience’s emotion; I particularly liked the use of a nervy violin at moments of high intensity, complementing Eddie’s gradual psychological and emotional decline. However, I believe that this is also a play that profoundly thrives on moments of quiet, yet music played throughout the action of the play, leaving only a few brief moments of genuine silence. There were times, particularly after the many outbursts of our leading characters, when I would have preferred to let their emotions linger uncomfortably for a little, rather than have them be slightly drowned out by music. But this critique is in no way intended to undermine the skill of the orchestra; the music itself was brilliant, even beautiful, and I enjoyed the slightly twisted Paper Doll motif that played at certain points in the production.

When it came to final applauds, I noticed that all of our actors seemed a little exhausted – and, after performing a play that epitomises “intensity,” I simply cannot blame them. But their hard labours have reaped rich fruits. Between their efforts and the creative direction of Morgan-Males (and, of course, the multitudes who have helped along the way!), Labyrinth Productions has staged a most profound and moving interpretation of Miller’s classic.

Even hours after watching the play, writing this review, I can still feel that knife’s edge. And that is a testament to a powerful production.

[A View from the Bridge, staged by Labyrinth Productions, is running at The Oxford Playhouse, 5th-8th Nov 2025]