I am a visiting law student from The University of Hong Kong, spending a full academic year at Hertford College. When I first arrived, I carried with me a suitcase, a reading list, and the quiet disbelief that I was finally here in Oxford, the place I had only ever seen in photographs.

The University of Oxford has always existed in my imagination as something distant and monumental: stone towers, cloisters, centuries of scholarship pressing quietly against the present. And now I live here. I carry my Bod card in my coat pocket. I complain about the weather. I rush to tutorials. The dream has become routine, but it has not lost its glow.

A different kind of academic rhythm

Studying law here has unsettled me in the most productive way.

In Hong Kong, our academic rhythm is reassuringly structured. A lecture typically begins with the foundations: the principles are explained, the cases are mapped out, the framework carefully assembled for us. We are shown the architecture of the law before being invited to critique it.

At Oxford, I was handed a reading list.

No introductory scaffolding. No carefully guided entry point. Just dense, demanding, unadorned pages and the expectation that I would arrive at the tutorial having already formed my own interpretation.

The first few weeks felt like intellectual vertigo. I missed the security of a lecture hall. I missed being told, explicitly “This is the starting point.” Here, there is no obvious beginning. You are expected to carve one out for yourself.

And yet, somewhere between confusion and determination, something shifts. The absence of structure becomes its own freedom. Instead of moving from A to B, learning feels like moving from zero to one. From constructing the framework yourself, discovering the argument rather than inheriting it, we are able to choose which tensions to explore, which doctrines to challenge, which footnotes to follow down unexpected paths.

The tutorial system amplifies this sense of autonomy. Most of my tutorials are one-to-one or one-to-two. The room is small. The conversation is direct. There is nowhere to hide and also nowhere to be silenced. We argue. We interrupt gently. We test each other’s reasoning. We are not simply answering pre-set questions; we are negotiating ideas in real time.

In Hong Kong, discussions often revolve around prepared tutorial sheets, and there is comfort in knowing everyone is responding to the same prompts. Here, the discussion can drift deliberately toward whatever we found most troubling, compelling, or unresolved in the readings. It is rigorous, occasionally intimidating, and deeply alive. I leave tutorials mentally exhausted and strangely exhilarated.

Candlelight, Gowns, and Borrowed Rituals

If the academic life here feels centuries old, so do its rituals.

Formal dinners have become one of my favourite parts of Oxford. There is something theatrical about descending into Hall beneath high ceilings, candles flickering against portraits whose eyes seem to follow you. Back in Hong Kong, we have something similar called the “High Table Dinner,” where the college masters sit elevated above the rest of us at the High Table. I once attended one at St John’s College in Hong Kong through a friend’s kind invitation — a rare privilege, since I did not live in a hall.

Here, formals are woven into weekly life. I have swapped formals with friends from other colleges, navigating unfamiliar staircases and sitting at long wooden tables where Latin mottos line the walls. It is part tradition, part performance, part community. I sometimes catch myself smiling at the absurdity of wearing a gown to dinner, and then realising how quickly it has begun to feel normal.

Living Alone — And Not Quite Alone

This is my first time living alone.

I imagined quiet evenings, perhaps loneliness. But during the term, solitude is difficult to sustain. There are always friends knocking on doors, always someone suggesting tea, always the temptation of a late-night walk. We crowd into rooms to play Monopoly. We debate case law one moment and argue about board game rules the next.

Still, there are small battles, like the ladybugs that appear unexpectedly in my room (they are still here above my lamp as I am working on this article). I never quite know how to deal with them. It is a peculiar kind of vulnerability — being alone in a historic building, staring at a tiny insect and feeling disproportionate fear. Yet even these moments become stories to laugh about later.

My flatmates are patient and kind. We share good news, stories, and sometimes snacks. There is a quiet intimacy in living alongside strangers who slowly become familiar presences.

Potatoes, Rain, and the Slow Sundays

Some culture shocks are intellectual. Others are culinary.

British meals are, in my experience, deeply committed to potatoes. In Hong Kong, meals are communal: dishes placed at the centre of the table, chopsticks crossing over one another, food shared without ceremony. Here, everyone orders their own plate. There is something efficient about it but also something slightly isolating.

I miss Hong Kong food more than I anticipated. I miss the noise of ‘cha chaan tengs’, the late-night options, the sense that the city is always awake.

Oxford feels quieter, especially on Sundays. Shops close early, sometimes by five in the afternoon. In Hong Kong, malls glow until ten at night. Here, the streets empty gently. I later learned that Sunday is often reserved for family — for home. Without a home here in that sense, the quiet can feel heavier.

And then there is the weather. The rain comes often and without drama. The pavements are uneven and unexpectedly slippery. I have nearly fallen more times than I would like to admit.

In the Space Between

Term breaks are the hardest.

When corridors empty and suitcases roll toward train stations, I remain. Hong Kong is too far for spontaneous returns. The distance stretches. The silence lingers.

I try to travel when I can. To step onto trains with no fixed plan. To make something in-between.

It is during these quieter weeks that I miss my family most, especially my mum and dad. During the term, the days are full and the loneliness is softened by lectures, tutorials, friends, and formals. But when everyone leaves for Christmas, the college feels hollow. The kitchen lights flicker on to no conversation. The staircases echo.

Last term, I fell seriously ill during the Christmas break. The kind of illness that makes you feel both feverish and strangely fragile. I remember standing alone in the kitchen, dizzy, cooking instant noodles for myself while running a 40-degree fever. The steam from the pot blurred my vision. There was no one to tell me to rest, no one to bring me water, no familiar voice checking whether I had taken medicine.

At that moment, Oxford felt very far from home.

There is a particular loneliness in being sick abroad. It is not just physical discomfort, it is the absence of the quiet care you take for granted. The knowledge that your parents are thousands of miles away. That if something were to happen, you would have to manage it yourself.

And yet, perhaps that is part of growing.

Yet when term resumes, the laughter returns to the corridors. Friends knock again. Tutorials resume their intensity. Life regains its rhythm. But that Christmas week remains vivid in my memory — not as a complaint, but as a reminder of what it means to be in between places.

Looking Ahead

This year is not permanent. I am here, and yet I will leave. That awareness sharpens everything — tutorials, formals, small friendships formed over shared cups of tea. There is urgency in knowing time is limited.

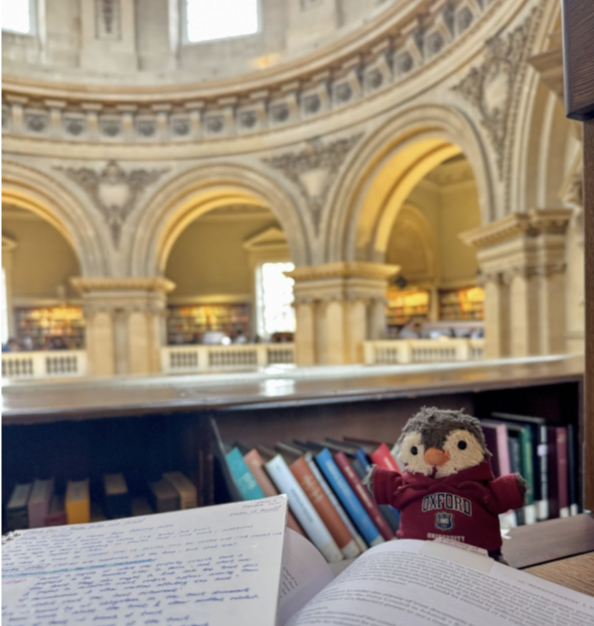

It has always been my dream to study at Oxford. I remember the thrill of receiving the offer letter, the moment when possibility became real. I remember my first time walking into the Radcliffe Camera, the first formal, the first night in my room when everything felt both foreign and full of promise.

Oxford has not been what I imagined. It has been slower in some ways, lonelier in others, and more intellectually demanding than I expected. But it has also been transformative.

I exist here in a kind of threshold — between Hong Kong and Oxford, between structure and freedom, between belonging and departure. It is not always comfortable, but it is deeply formative.

And when I eventually leave, I know I will carry this year with me like a book whose pages I once stepped inside, lingering long after I return to ‘Home’ Kong.